Continuous City

Historic lessons of urban design applied to new high-density developments.

Paul L. Whalen, FAIA

Grant F. Marani, AIA, FRAIA

Bina Bhattacharyya, AIA

Chen-Huan Liao, AIA

A high-density urban habitat must engage the public in a walkable setting that unfolds as a coherent but multifaceted experience. In our paper “Continuous City,” published by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, we outline strategies to create compelling, navigable social environments in three large-scale master planning projects.

As cities grow denser, governments, developers, architects, and planners must prioritize the vitality of the human experience that leads people to gather in cities in the first place. Successful planning for urban communities requires attention to the fine-grain pedestrian experience: the creation of lively streets that encourage walking and human interaction. City-dwellers expect their environments to provide a sense of order, to help them find their way, but also variety, to keep their interest and support many different lifestyles.

Learning from Manhattan

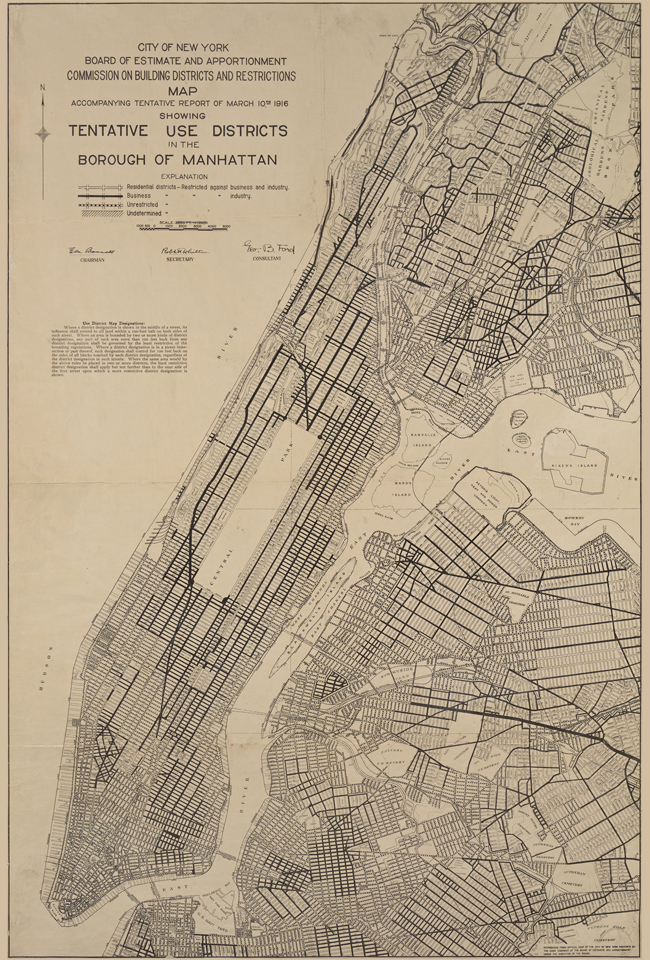

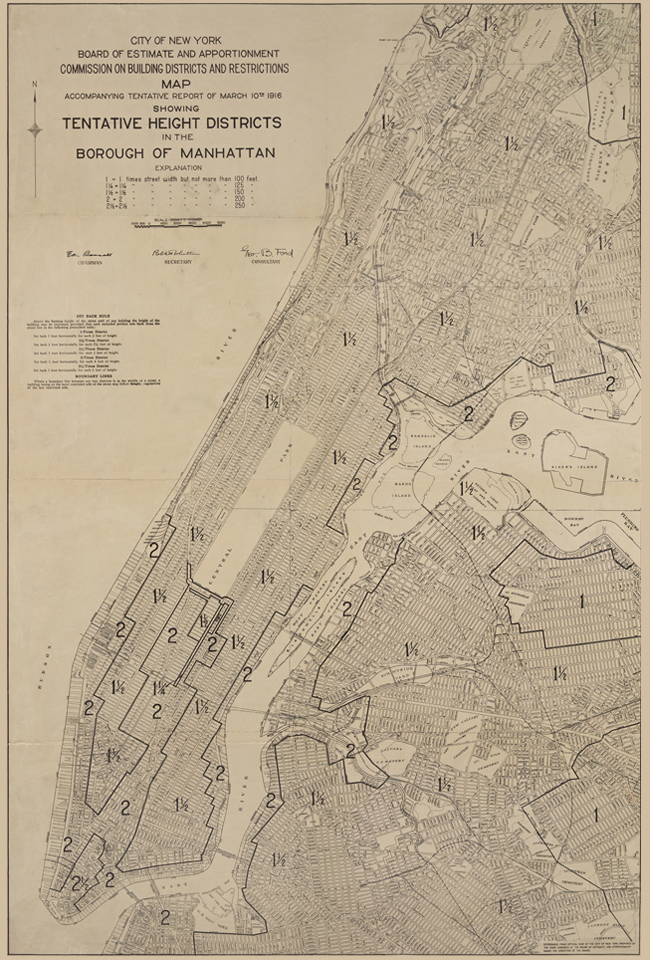

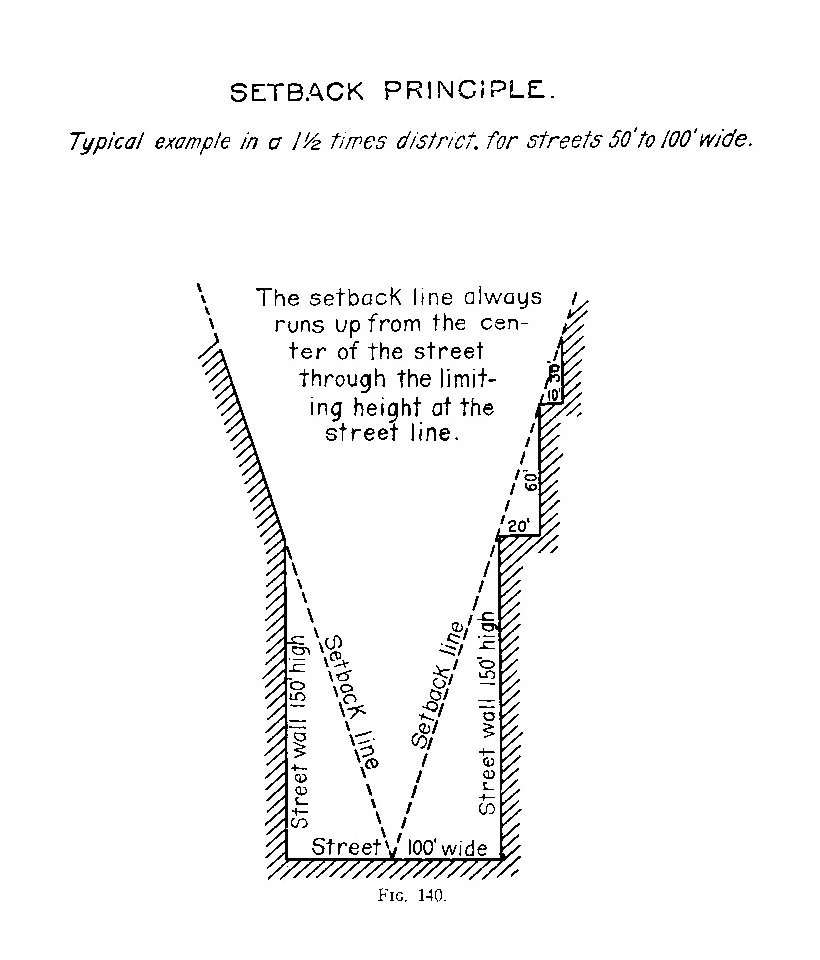

We are continuously inspired by our own home city of New York. On the gridiron plan first mapped across Manhattan Island in 1811—itself a direct descendant of the classical Roman town plan, though at a vastly larger scale—early experiments in buildings of great height were promptly balanced with regulations aimed at preserving the essential qualities of a hospitable city. The 1916 Zoning Resolution, conceived to ensure that new skyscrapers would not prevent light and air from reaching the street, guided the location and shaped the forms of the city’s first generation of towers. This led to a juxtaposition of tall buildings along Manhattan’s broad avenues, with mid-rise buildings and row houses lining the city’s narrower side streets.

Historical maps of Manhattan noting tentative use districts from New York City’s 1916 Zoning Resolution. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Diagram of the setback principle introduced in New York City’s 1916 Zoning Resolution. Source: Bassett, Edward M. Final Report on New York City’s Zoning Resolution. New York: New York Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, 1916.

Beyond the general order established by zoning, the individual New York city block merits closer analysis. A typical Manhattan block accommodates buildings of a range of scales, the taller buildings at the east and west block ends bracketing lower buildings along the side streets. This allows southern light to penetrate the center of the block. Even when real estate pressures led to the incorporation of taller towers, zoning required that their massing be sensitive to their lower neighbors. Along the avenues, shopfronts engage passersby, serving residents’ needs within comfortable walking distance of their homes, while on the side streets, articulated row house entrances maintain a human scale.

Pre-World War II New York enjoyed an architectural culture that applied principles of Western classicism, such as a system of proportion, a language of ornament, symmetry within variety, and brick and masonry expression so that buildings at all scales conversed in a common rhythm and palette of materials. Rather than towers standing as isolated objects, consideration was given to how they met the street, with shopfronts, fenestration, and ground-level detail. Standing side-by-side with lower-scale neighbors, they participate in a continuous pedestrian experience.

After World War II, new theories about order and rationalism in design led to the development of isolated high-rise towers and endlessly repetitive residential slabs, creating disjointed cityscapes that discouraged walking and weakened a sense of community. Despite this model’s recognized shortcomings, the urgent need for housing in today’s rapidly expanding cities has allowed this easily replicated form to persist.

Heart of Lake, Xiamen

Building Blocks

In 2009, our firm was asked to design a 200,000-square-meter residential development, Heart of Lake, on a peninsula in Xiamen, China. Bringing to the assignment lessons learned in our study of New York’s prewar urbanism, our design advocates for a variety of building scales, adding a mix of mid-rise and low-rise residential buildings and townhouse rows to the given program of high-rise towers and freestanding villas. We combine these types to form blocks, with taller buildings on broader north-south boulevards and lower buildings along narrower streets.

At Heart of Lake, towers are located to minimize afternoon shadows; mid-rise buildings face north-south streets; low buildings face east-west streets; villa rows face the lake; and intimate paths defined by garden walls incorporate tea houses in private gardens. Photographs RAMSA, 2013–19.

Here’s where New York’s influence ends and local and regional influences begin. For inspiration, we looked to Gulang Island, a nearby historic neighborhood featuring traffic-free streets winding about the natural topography. This pattern, infused with lush tropical gardens, informed the layout and landscape design of Heart of Lake. Our master plan is centered on a broad park oriented to capture prevailing breezes during Xiamen’s long tropical summers. The street grid has a slight radial twist so that, despite a clear awareness of north-south or east-west orientation, pedestrians encounter ever-changing perspectives as they walk across the community. The rich and varied experience of this entirely pedestrian neighborhood is a marriage of the walls and gardens of a traditional Chinese village with the organization of a New York city block.

AVIC International Square, Dalian

Pedestrian Destination

AVIC International Square, a much higher density project than Heart of Lake, fronts a key urban thoroughfare connecting a string of important civic plazas along its length. We developed the five-hectare site as four blocks divided by streets that tie into the existing grid. Eight strategically placed residential towers, two office blocks, and a forty-story office tower flanked by lower wings provide a complete live-work environment in a fine-grained urban setting.

For International Square, we drew lessons from another New York prewar model: Rockefeller Center. Conceived and realized as a single endeavor, the first iteration of Rockefeller Center occupied four blocks in the heart of the Manhattan, creating a new urban core. The development has proved its enduring value, both as an integral part of the city’s life and as a tourist destination, weaving a variety of building scales, public space, and retail shops into an existing urban fabric.

International Square’s blocks are wrapped at the ground level with shops. Storefronts define streets and mid-block passages that frame a variety of gardens, courtyards, and public plazas. Open spaces also provide porosity and pedestrian circulation throughout the quadrants of the development. These attractive pedestrian destinations generate a streetscape fully integrated into Dalian's pre-existing city life.

Following the example of Rockefeller Center, a landscaped setback faces the main thoroughfare and establishes a sense of place, broadening the boulevard to offer an inviting, accessible entrance at AVIC International Square, Dalian. Rendering RAMSA, 2013.

AVIC Jinjiang Uptown

Expandable Communities

Larger still is AVIC Jinjiang Uptown, a residential and retail townscape on 235 hectares. Whereas AVIC International Square plugs into an existing grid, AVIC Jinjiang Uptown lies at the edge of a rapidly growing city, where it will set the pattern for future development.

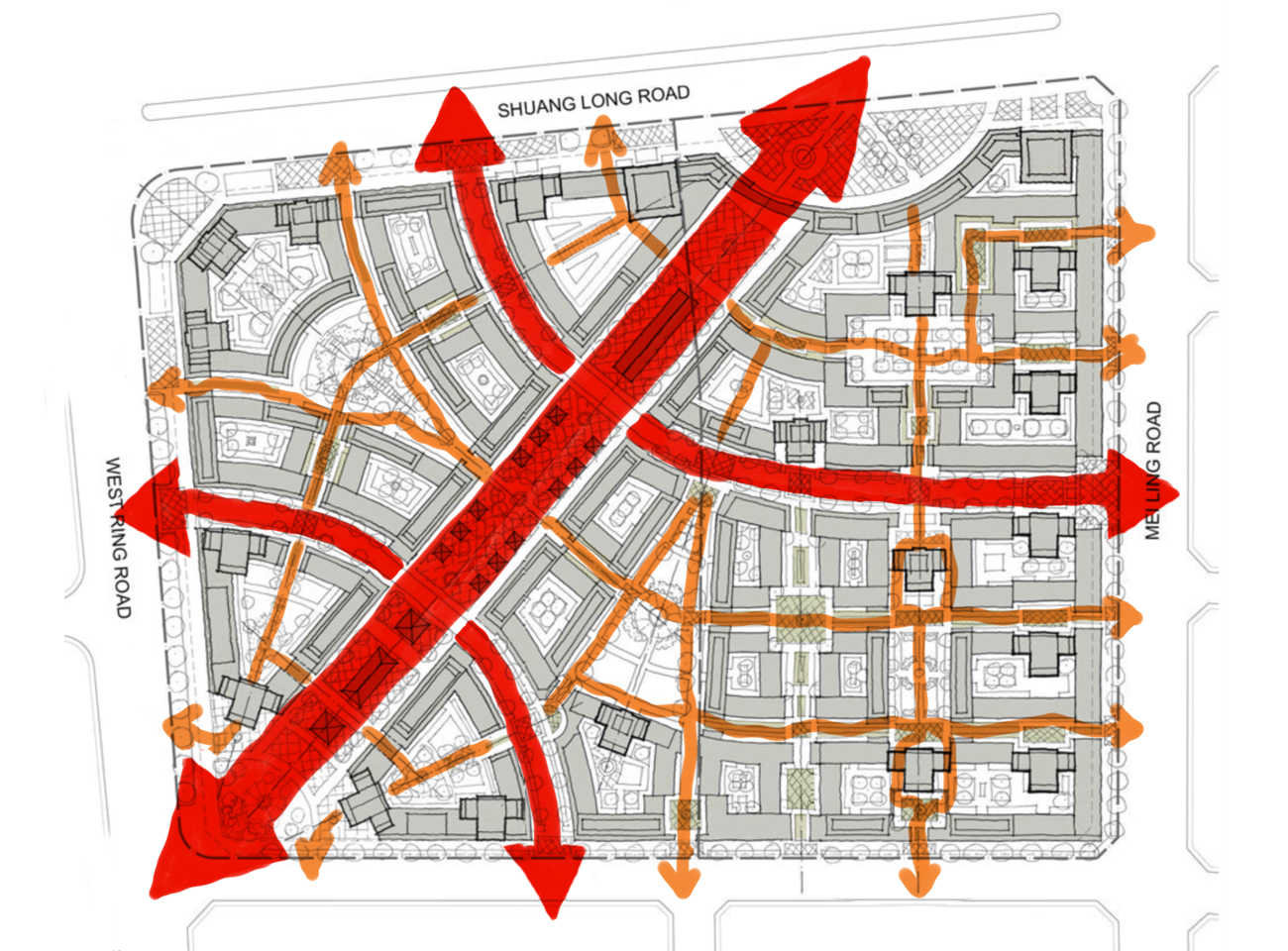

To attain the required density and mix of uses in a lively, walkable urban community, we again applied the lessons of New York’s ideal city block. Facing the major arterial road that runs along the north edge of the site, we developed a welcoming plaza, a great arc lined with retail that leads to a broad diagonal boulevard, preserving a protected view corridor that runs through the site. This boulevard is fully pedestrian; it will serve as a linear town square for the community and as a shopping destination for visitors from around the city. Two crescent streets—the only streets open to cars—connect north to east and west to south, introducing unfolding picturesque views as they provide permeability to this large site.

AVIC Jinjiang Uptown site plan sketches indicating the main boulevard and curving grid of streets; pedestrian and vehicle circulation; public and private courtyards and gardens. Diagrams RAMSA, 2018.

To further break down the scale of the community, shop-lined streets define seven smaller neighborhoods of varying shapes and sizes, each with its own residential and retail components. The largest of these are divided into residential blocks that, like in Manhattan, accommodate a hierarchy of building types and scales, allowing us to define wide and narrow streets, mews, and plazas.

The urban garden-like quality of Shanghai’s former French Concession district with curved tree-lined streets, trellised pathways, and intimate pocket parks inspired AVIC Jinjiang Uptown’s network of greenery threaded throughout with landscaped pathways, parks, and shared gardens. Side streets with small shops and single-story homes mix with towers sited to meet stringent light and air requirements. These elements, combined and overlaid on a legible grid, engage and support the activities of pedestrians.

Looking Backward and Forward

In these projects—Heart of Lake, AVIC International Square, and AVIC Jinjiang Uptown—we integrated traditional and new patterns of development to best suit our clients’ present and future goals. High-density neighborhoods with an ever-increasing proportion of tall buildings represent the future of urbanism worldwide. We advocate for the continuous urbanism of the world’s best cities while also recognizing that the lessons of the past can continue to support our cities into the future.