Fourth Generation Libraries

Tracking the evolution of library design in the United States.

Alexander P. Lamis, FAIA

Library design is a topic of great personal and professional interest to me. I have been involved with RAMSA’s library projects over the past two decades with over twenty projects across the United States from northern Maine to southern California. These include public libraries, university libraries, and even the extremely rare presidential library. Over the last twenty years, we have had a front row seat to social and technological developments that have caused us to reimagine what a library is and what it can be. Many of the old rules have been thrown out the window, replaced with innovative and inspiring proposals for what comes next. I would argue that change did not begin with the internet, but rather that change has often been the norm in the history of library design. For example, the idea that libraries should contain more than books is hardly a new one. When the public library in Braddock, Pennsylvania, opened in 1890, it included a swimming pool, public baths, bowling alleys, an art gallery, a gymnasium, and a billiard hall.

I think library buildings in the United States can be grouped into four successive design generations. From colonial times to the end of the nineteenth century, most library collections were relatively small, and either private or available through subscription. The period from approximately 1880 to 1940 saw the creation of great library edifices paralleling the proliferation of colleges in the United States and the public library movement. Books and other materials moved out of closed-stack storage in the great wave of growth and suburbanization after World War II. Today we have embarked on a new generation of libraries that blend the material and the ethereal—a new hybrid building type.

First Generation

The Private Library, 1700–1880

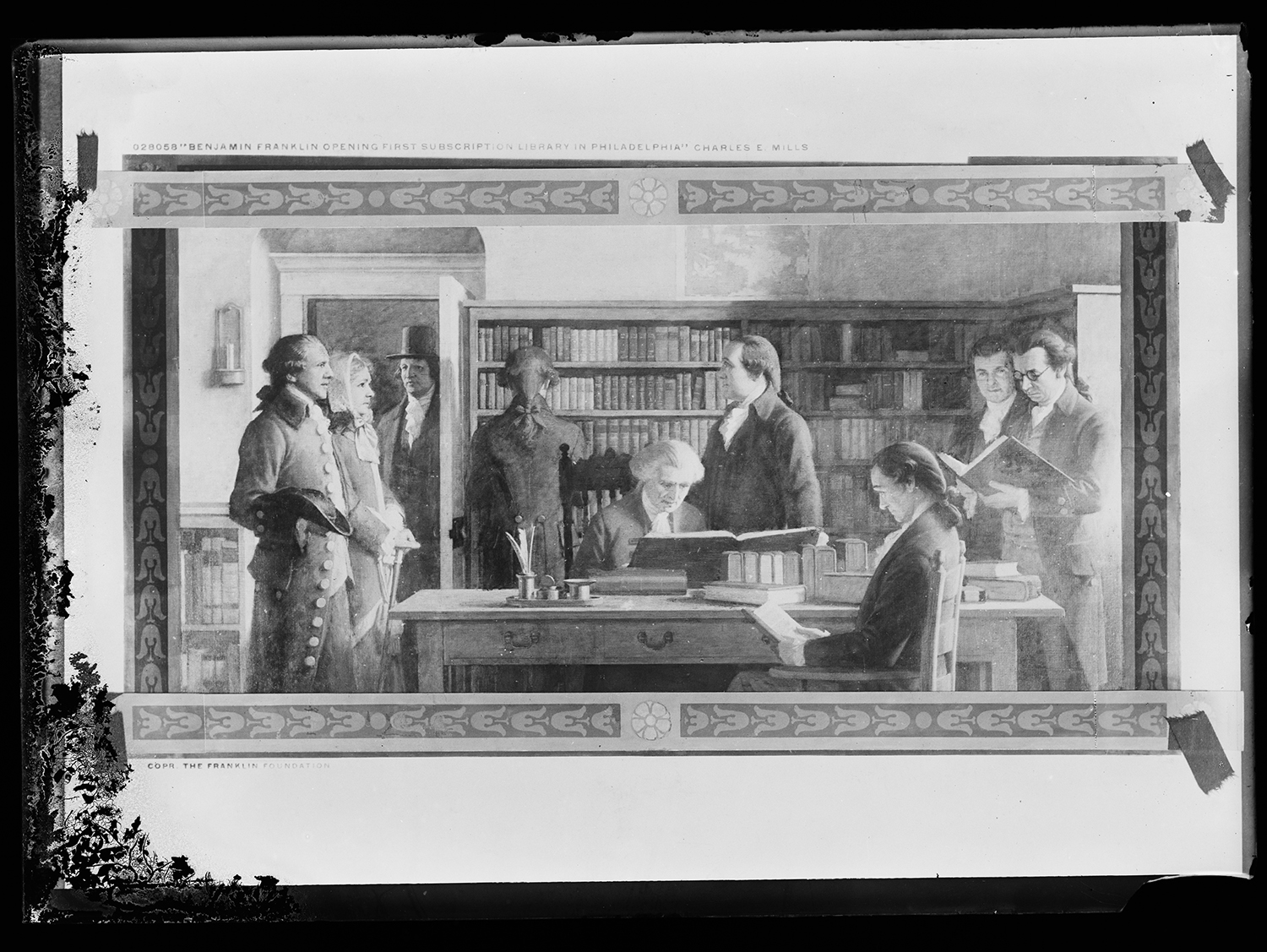

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, purchasing books was prohibitively expensive for most Americans. Only the very wealthy could amass sizeable book collections, which were housed in “gentlemen’s libraries.” In 1731, Benjamin Franklin spearheaded a plan to make reading materials more widely accessible. He and other book owners pooled their resources and collections into one large lending library. This effort became the Library Company, the nation’s first subscription library, which allowed anyone to borrow material from the library for the cost of an annual membership fee. The idea gained traction and similar subscription libraries opened in other cities.

Benjamin Franklin opening the first subscription library in Philadelphia (Charles E. Mills, c. 1912). Photograph of a mural, dry plate negative. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Second Generation

The Public Library, 1880–1940

The second generation of libraries emerged during the second half of the nineteenth century, when intense changes in American cities—an influx of immigrants, rapid industrialization and urbanization, and the prevalence of political corruption—spurred calls for major reform. Proponents of the Progressive movement sought to reform a variety of aspects of American life, but a focus on public education as a tool for social improvement was foremost. Simultaneously, an architectural and social philosophy known as the City Beautiful movement was influencing urban planning. Advocates of City Beautiful believed that civic grandeur and monumental architecture would inspire civic virtue.

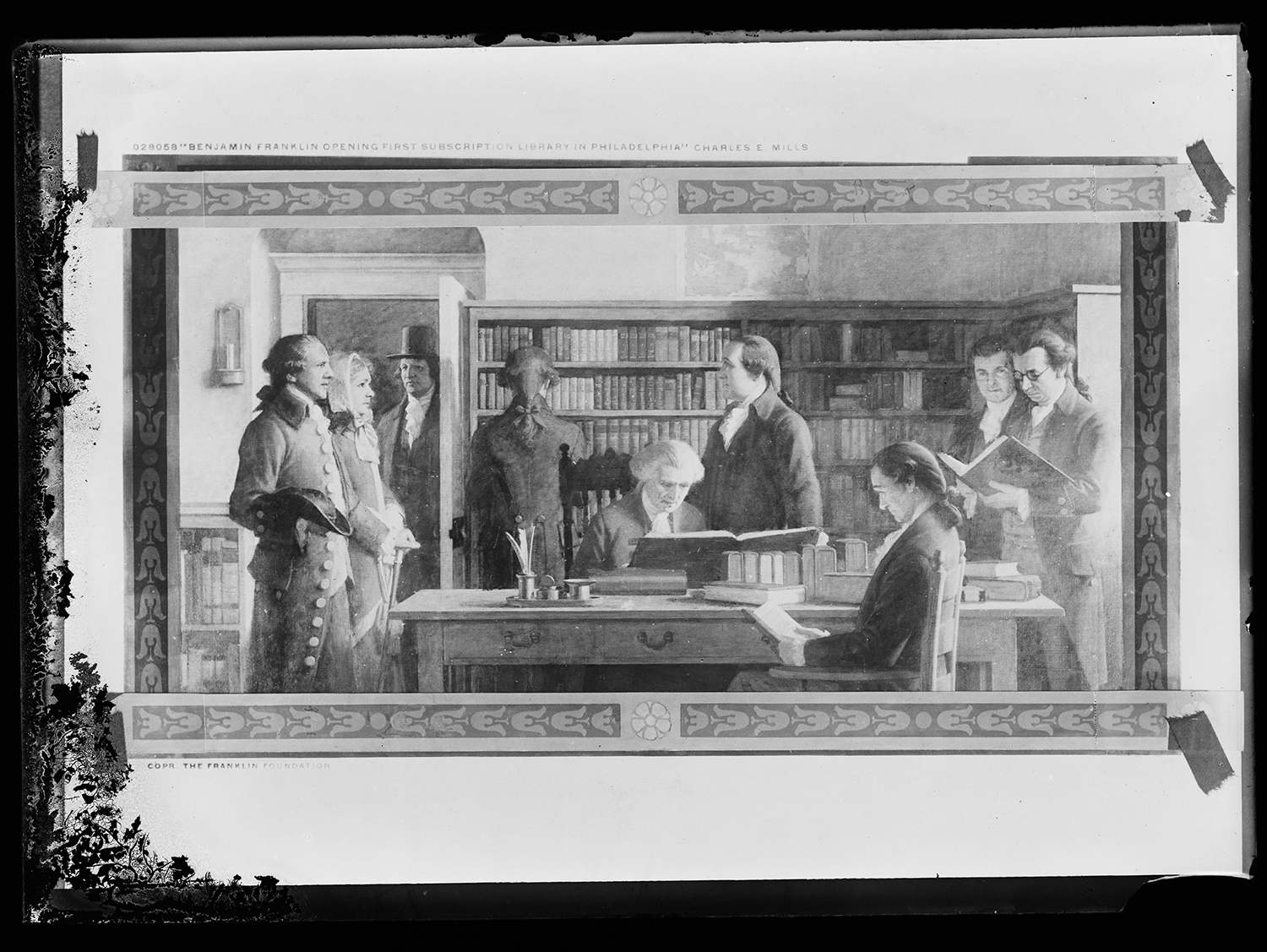

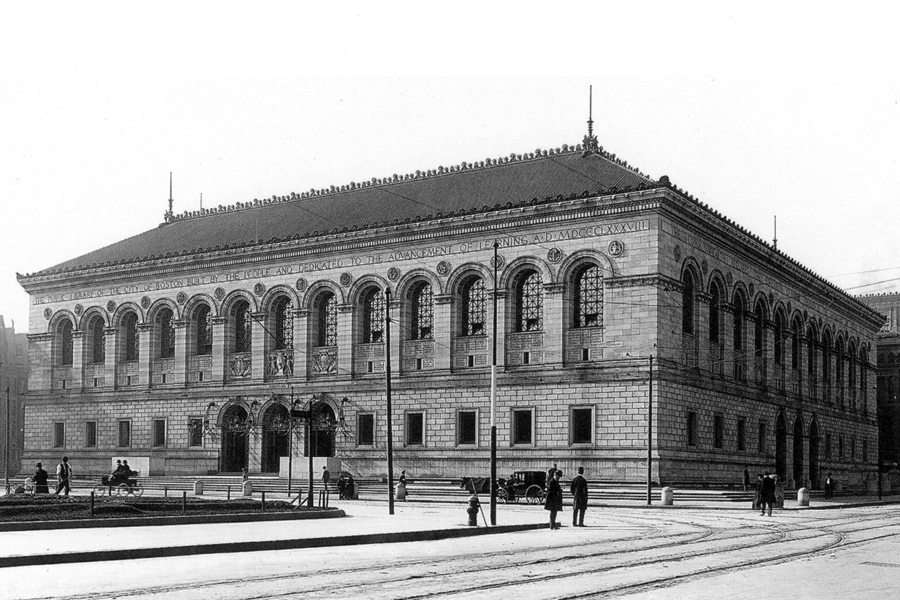

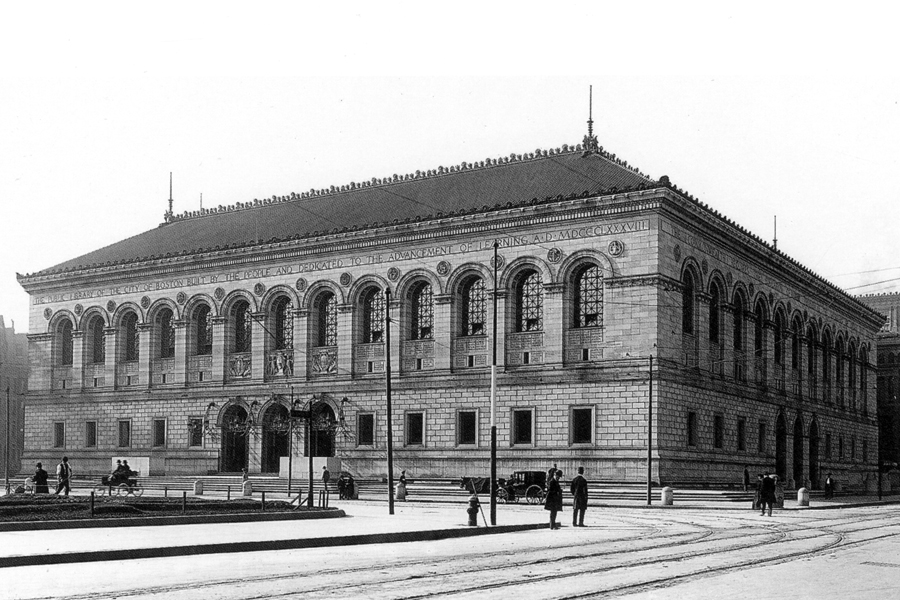

Boston Public Library (McKim, Mead & White, 1895). Photograph c. 1900. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The outcome was a series of grand public buildings that are still celebrated today, such as the central branches of the Boston Public Library and the New York Public Library. Most of the large libraries built during this period were planned in a similar way, with collections kept in a stack core closed to the public. Materials were requested by written orders and then used in reading rooms, many with high ceilings, large clerestory windows, and richly ornamented and often allegorical wall surfaces.

In the same period, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie funded the construction of thousands of libraries in cities and towns across the country. These “palaces of the people” were also designed with civic virtue in mind, although often on a much smaller scale. Unlike previous closed-stack libraries, users could directly access books stored in public, open stacks.

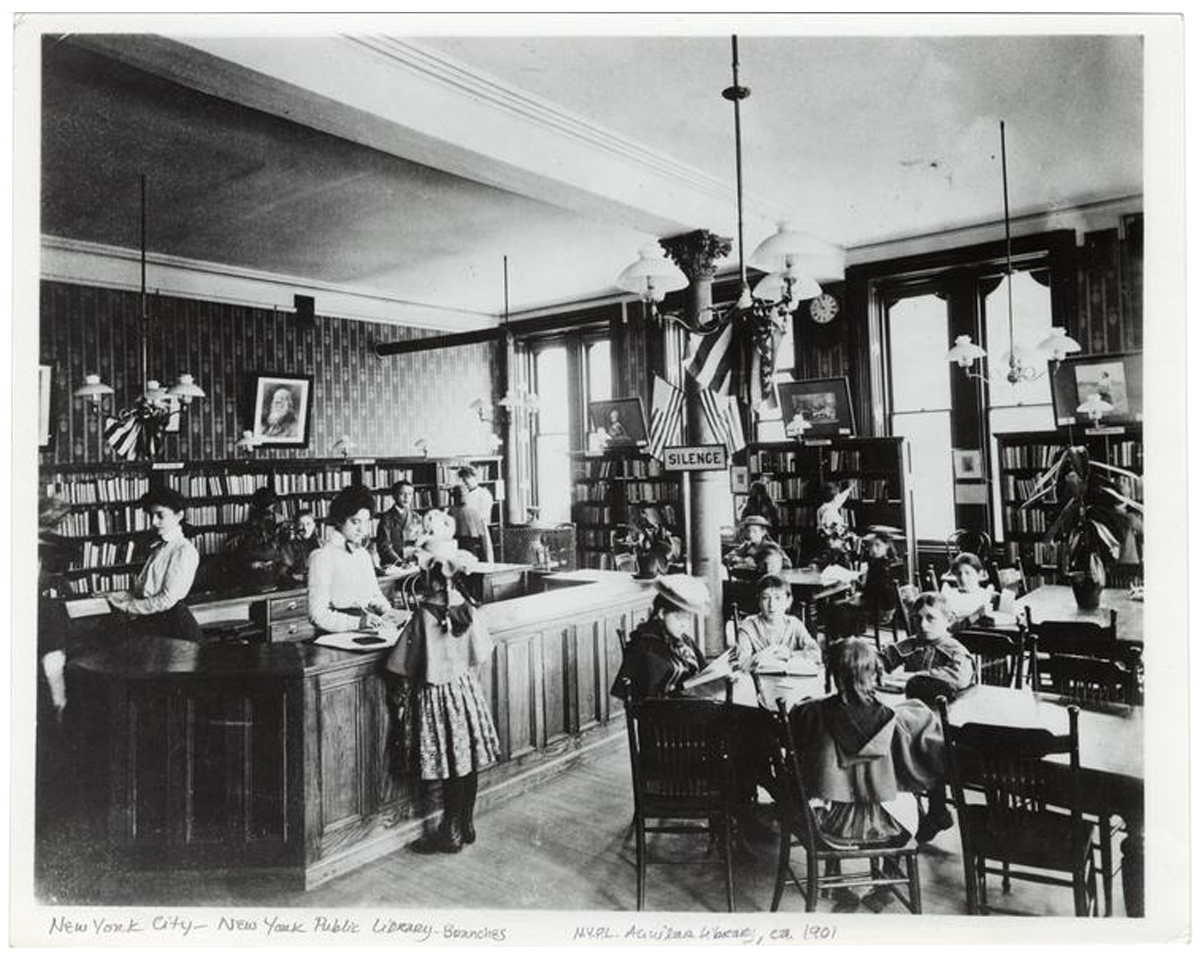

Historic photographs of New York Public Library branches funded by Andrew Carnegie. Photographs c. 1901–10. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs.

Third Generation

The Open-Stack Library, 1940–90

Powerful social and political changes in the United States after World War II propelled an explosion in the construction of public libraries. Suburbanization distanced people from downtown libraries, the civil rights movement pushed for equal access to public libraries, and government funding was made available in the 1960s to support both public and academic libraries. These new libraries followed the successful model of Carnegie libraries. Closed stacks were replaced with a modular and egalitarian open-stack arrangement. Bookstacks and patron seating, instead of being separated, were mixed together. Flexibility was key: the fewer walls and rooms, the better.

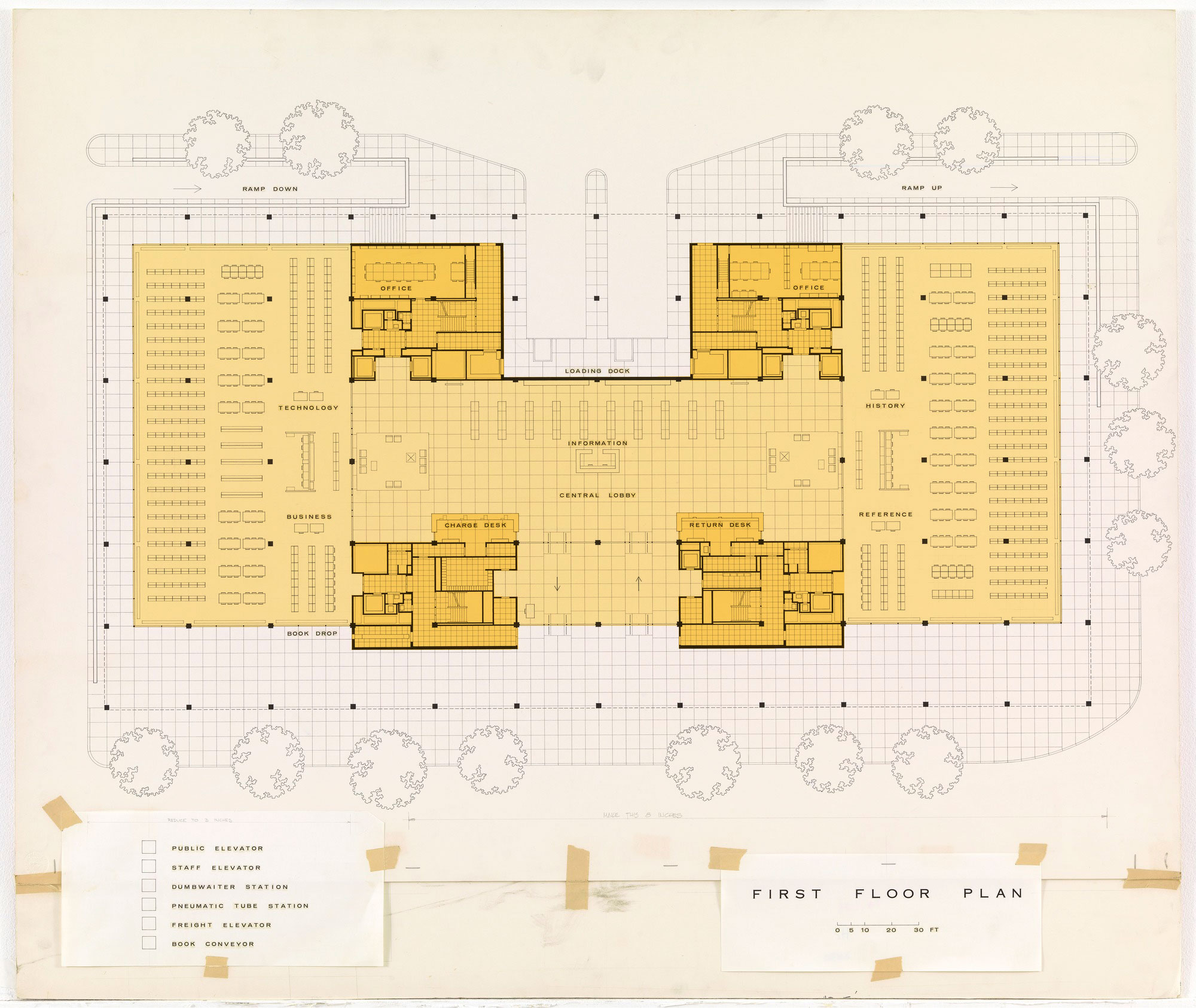

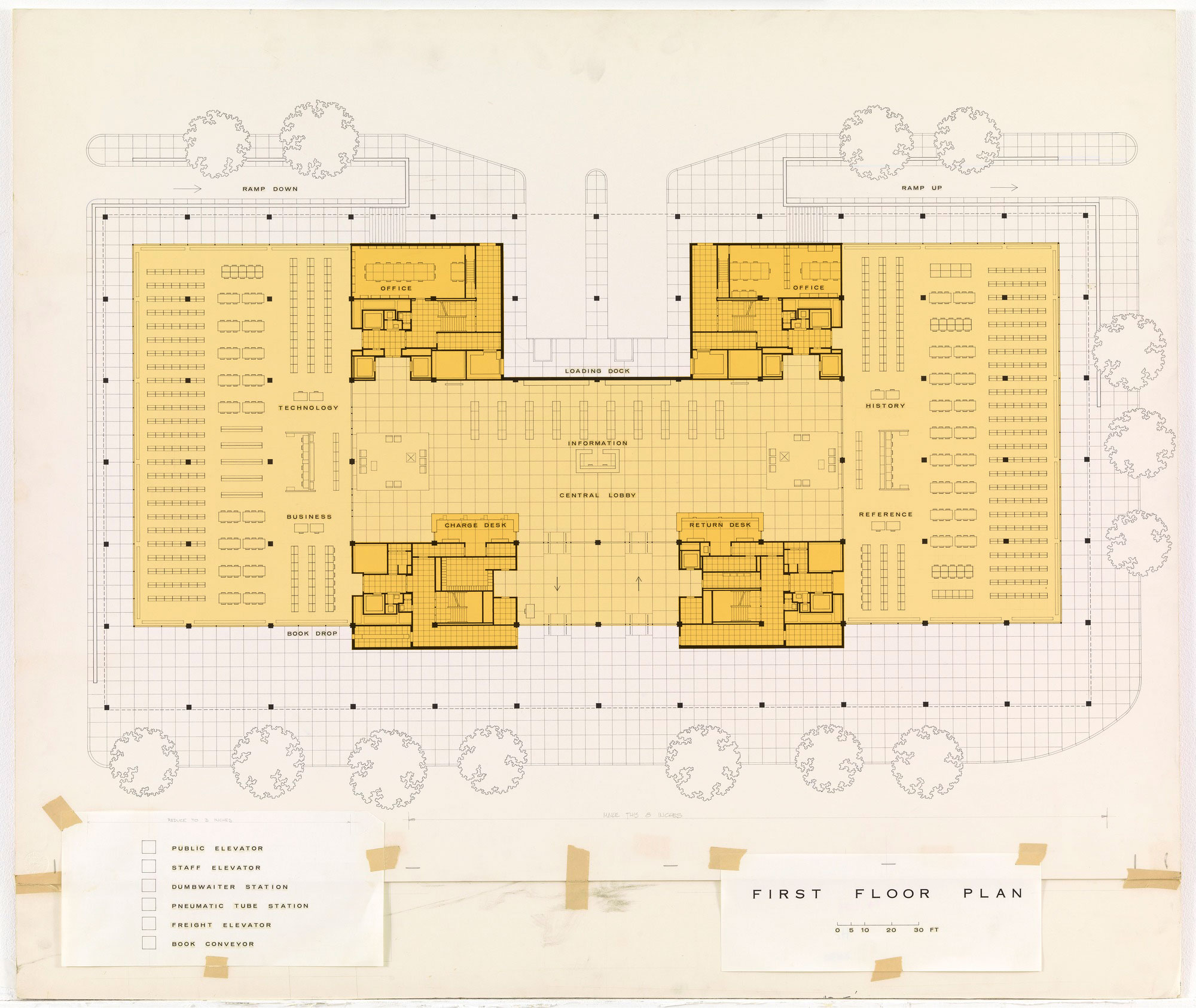

Martin Luther King Jr. Library (Mies Van der Rohe, 1968), Washington, DC, first floor plan. Source: Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Fourth Generation

The Hybrid Library, 1990–Present

Today, we are in the fourth generation of libraries, which began with the widespread use of the personal computer in the 1990s and has accelerated with the explosion of internet use, communications technologies, and most recently machine learning and artificial intelligence. Library design is responding to external changes that tend to undermine the traditional use of the library building as a repository.

Our own library projects exemplify this hybrid type—buildings that accommodate a wide range of services intended to support the advancement of knowledge and strengthen the communities they serve. On any given day, more than ten thousand people walk into a library that our office had a hand in designing and bringing into being. A few examples stand out as reflections of the impact technological, social, and economic developments on this typology.

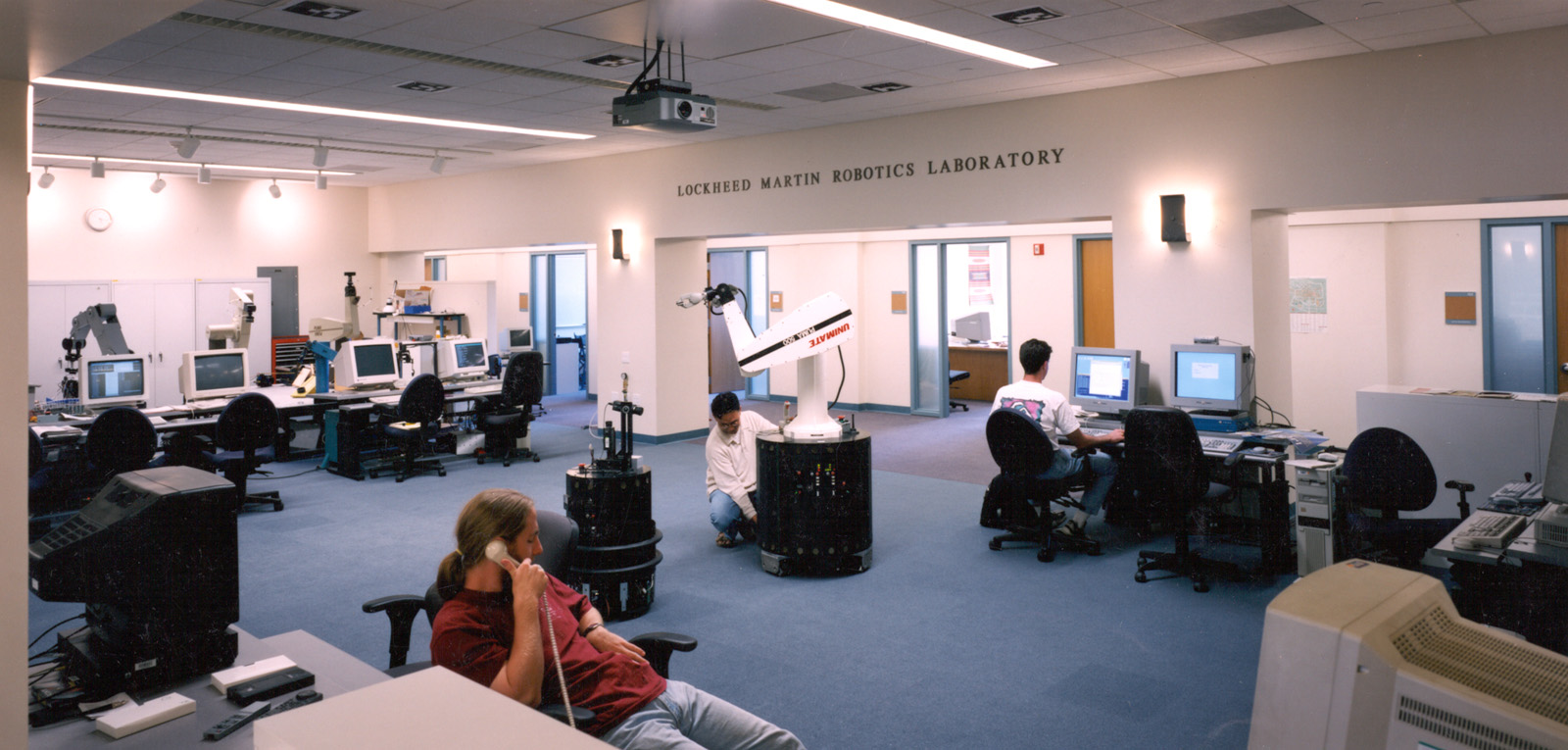

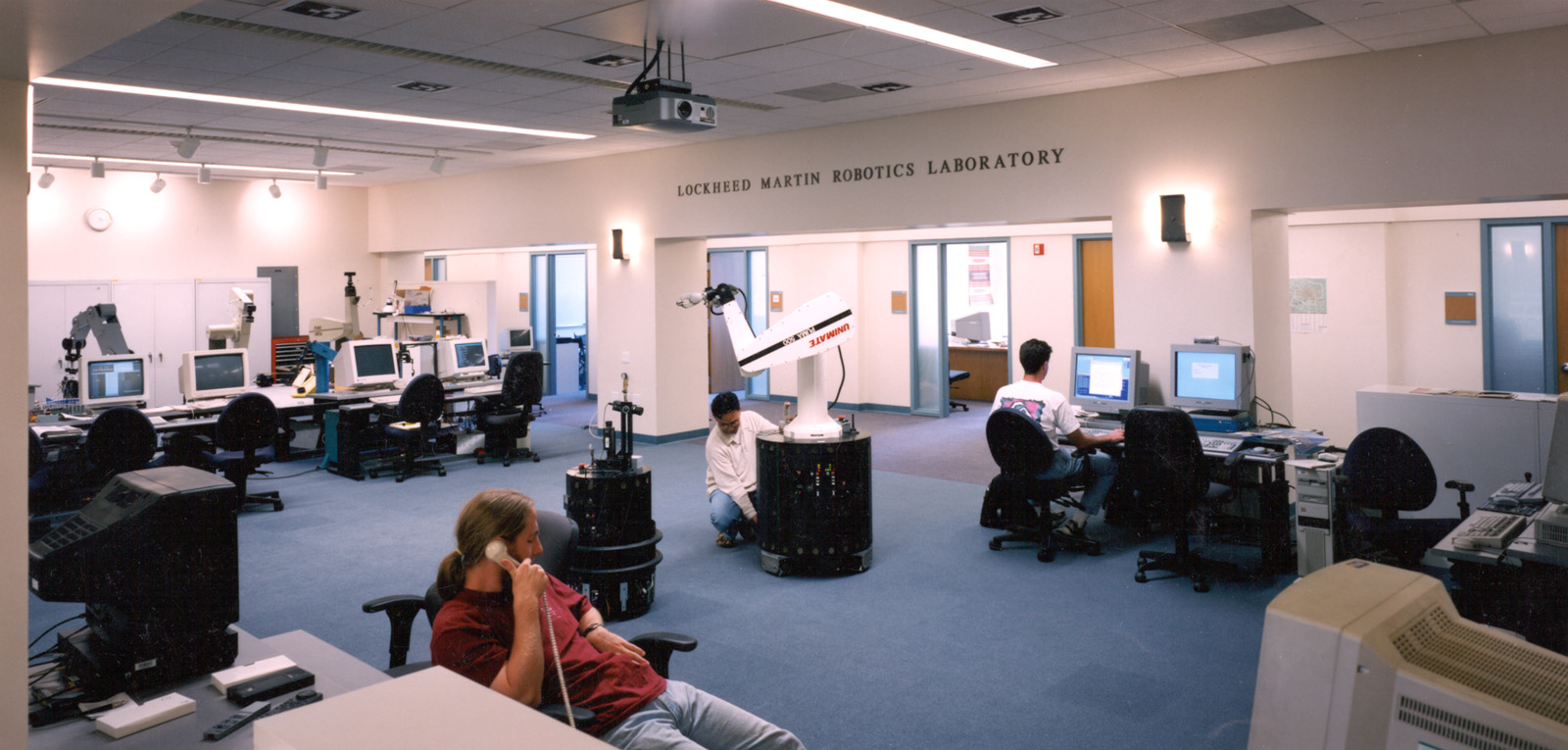

While not a straightforward library, the William Gates Computer Science Building at Stanford University (1996) was built at the onset of this transitional period. The building was initially designed with cables in trays near the ceiling of every office so that faculty could reconfigure connections to meet their needs. During the design, the dean said we may be able to do away with all the open cables because he was on the board of a new company called Cisco that had designed a device called a router that did the same things without the need for physical rewiring. This forethought was critical to maximizing the potential of the building as a long-term investment for the university.

Robotics Lab in the Gates Computer Science Building, Stanford University (RAMSA, 1996). Photograph Peter Aaron / OTTO, 1996.

At the Harvard Business School, we transformed the Baker Library into the larger, more flexible Baker Library | Bloomberg Center (2005) by replacing the original self-supporting stack cores with a multi-functional building that combined the school’s library and archives with new faculty offices, seminar rooms, and lounges. Doing so preserved the distinguished architecture of the McKim, Mead & White–designed facade, while modernizing the library’s services and facilities.

Baker Library construction progress. Photographs RAMSA, 2003–05.

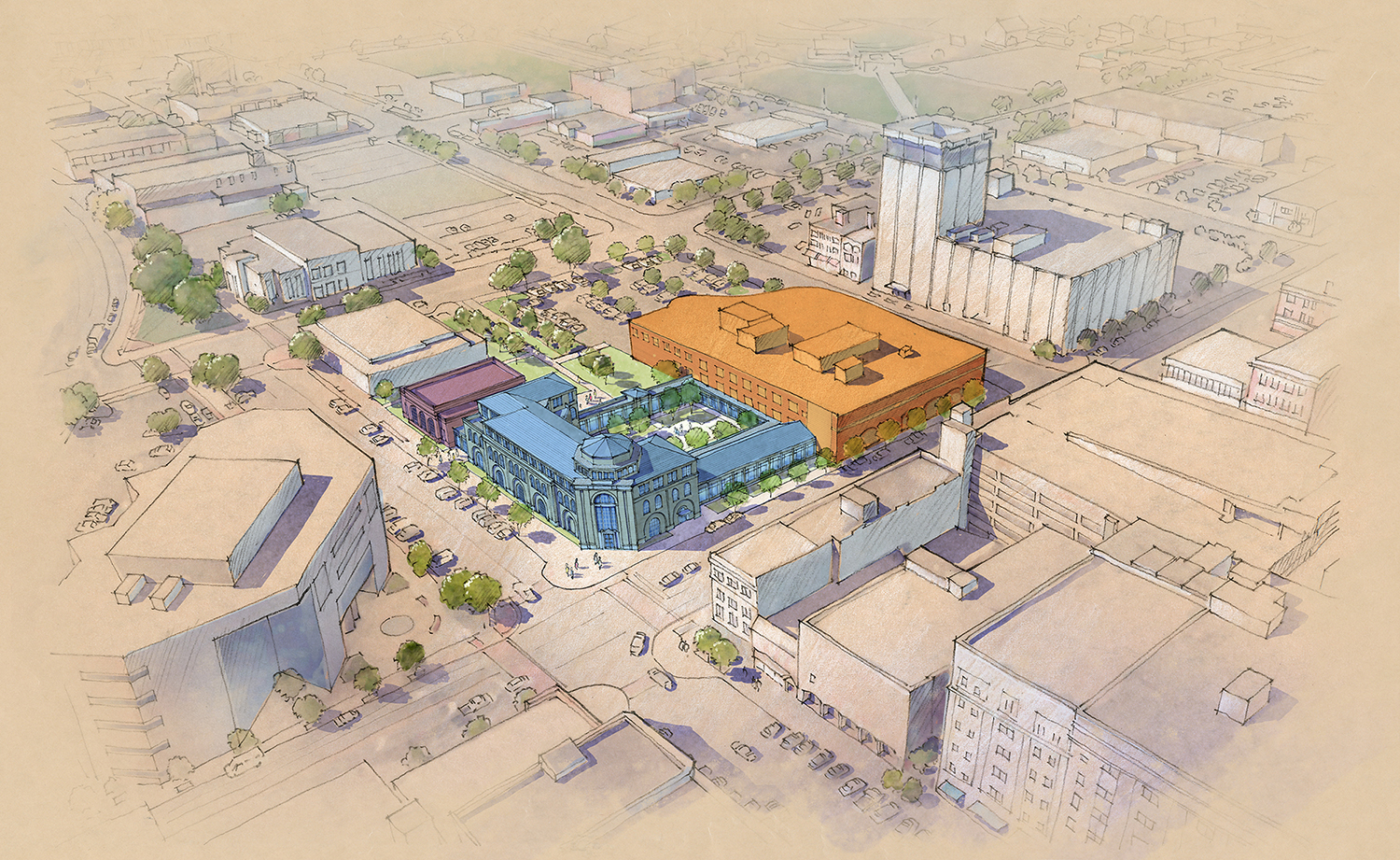

Another characteristic of contemporary libraries is an intentional focus on community service and an openness to collaboration with other groups or institutions. In South Bend, Indiana, we were hired to work with the public library on a renovation and addition that incorporates a series of partnerships intended to strengthen educational resources and employment opportunities for the local population.

Like many other rust belt cities, South Bend faces high levels of poverty and unemployment, resulting from dependence on the declining automobile manufacturing industry. For downtown South Bend, the St. Joseph County Public Library (in design) meets these challenges and acts as a major positive social force. A city-wide pilot program is developing South Bend as a “City of Lifelong Learning.” The basic premise is that people—regardless of their age, educational level, income, or job status—deserve ongoing educational resources and credentialing outside of a formal education system. The Lifelong Learning program aims to help users meet their personal, professional, and educational goals through personalized assessments and suggested coursework.

The St. Joseph County Public Library will be one of the lead local agencies implementing the Lifelong Learning program. In terms of the design, this means we will include what is essentially a school within the library: classrooms, seminar rooms, a 250-seat auditorium, one-on-one tutoring rooms, and a technology center, in addition to mainstays of public libraries everywhere, such as children’s services and departments for teens and local history. When completed in 2021, the library will be a central hub, with a blended on-site and online presence, that will act as an active and major participant in the creation of opportunities for South Bend’s residents, and as an engine for economic development over the long term. This project suggests an exciting future for libraries that blends traditional services and strengths with entirely new services made possible through both social and technological innovations.

St. Joseph County Public Library interior spaces. Left to right: technology center, study area, makerspace, children’s reading room. Renderings RAMSA, 2018.