Polychromy on Park Avenue

Ruminations on RAMSA’s neighboring building, Two Park Avenue.

Leopoldo Villardi

With the fast-approaching anniversary of our office’s transition to remote work, the overwhelming impact of the pandemic could not be more clear. For those of us privileged with employment and the ability to work remotely, the absence of once-familiar spaces has short-circuited our everyday lives. Without shared office kitchenettes, there is no place for happenstance conversation; without access to our extensive office library, there is no table to sit and devour books. The urban fabric and architectural backdrop so closely associated with our ritual commutes has all but evaporated from our immediate consciousness. For me, I especially miss the social gatherings with colleagues over lunch or drinks on our office’s landscaped terrace, which offers up an incredible view of Midtown Manhattan’s skyline anchored by a fascinating building: Two Park Avenue (1926–1928).

Despite their differences, One Park Avenue (where our office is located) and its art deco counterpart across the street share a common history. Both speculative office buildings were developed by Henry Mandel, who acquired the two lots in the 1920s (and with them a decrepit car barn and a failing hostelry) on what was then called Fourth Avenue. The neighborhood was still primarily residential at the time, but the experienced developer knew how to convince prospective commercial tenants to sign on. To offer up the tantalizing addresses of numbers One and Two, his syndicate successfully campaigned the city to extend Park Avenue southward by two blocks (much to the chagrin of Martha Waldron Cowdin, who lost multiple lawsuits to maintain her original address of One Park Avenue at 34th Street). [1] Mandel also hired first-rate designers for the buildings: well-known bank architects York & Sawyer for the east lot and emerging commercial specialists Buchman & Kahn for the west.

One Park Avenue (York & Sawyer, 1925) and Two Park Avenue (Buchman & Kahn, 1926–28) around the time of their completion. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collection and The Architectural Record v. 63, n. 4 (April 1928), respectively.

One and Two Park Avenue were designed when tall towers were rapidly springing up across New York City in the manner of Hugh Ferriss’s fantasies first published in Pencil Points, but number Two went much further in capturing the spirit of the moment. Unlike Ferriss’s black and white charcoal renderings, the building is a polychromatic gem, with tones that change throughout the day and shadows that dance with the passing sun. It was delightfully contemporary for its time, with myriad eclectic details, clear structural expression, and pragmatic massing, aspects for which it received high praise from critics like Lewis Mumford. [2] Mandel’s strategy worked, and companies including furniture producers Thonet and Herman Miller, as well as shirt and collar manufacturers Cluett, Peabody & Co. leased office and showroom space in the two buildings.

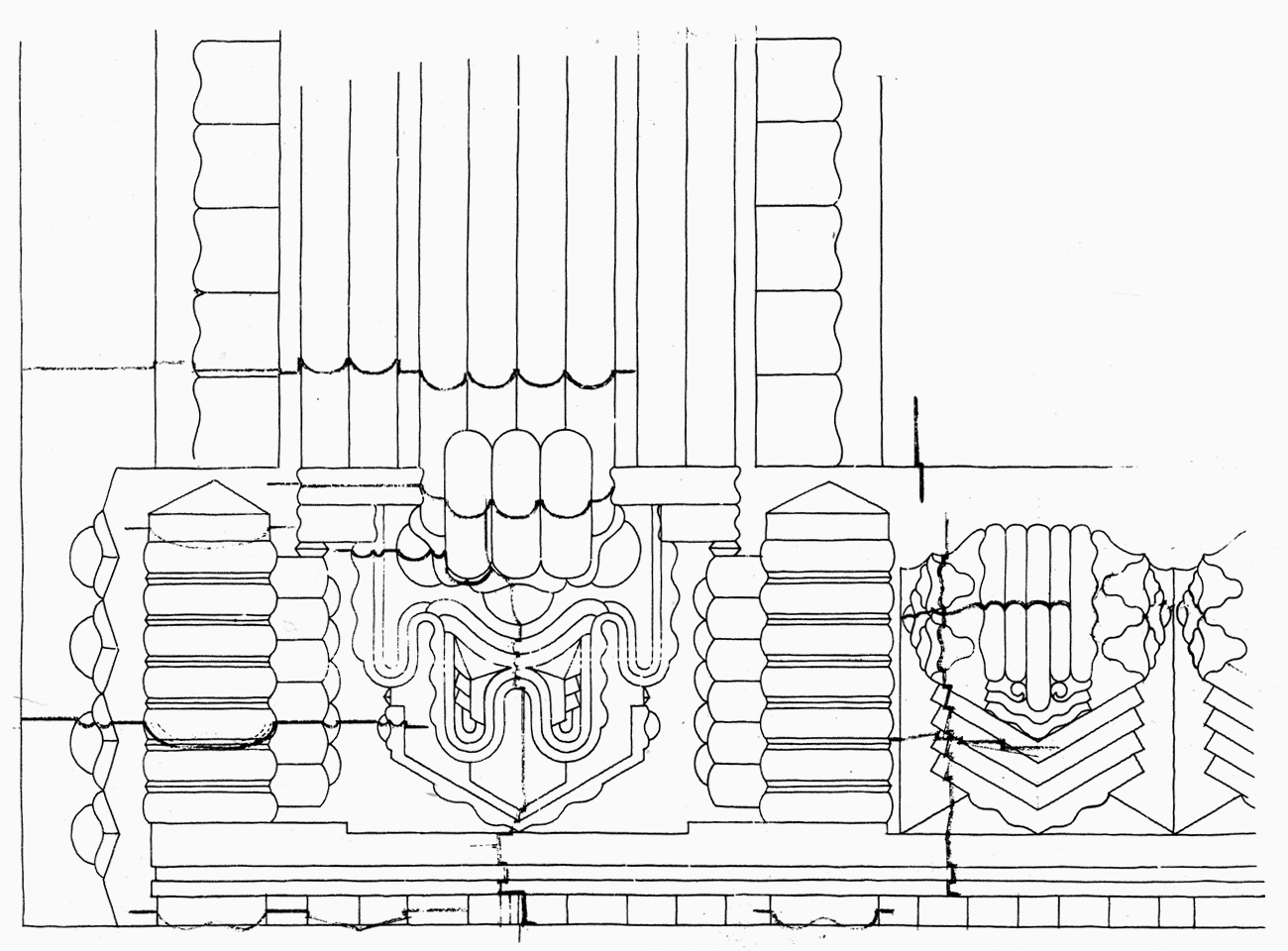

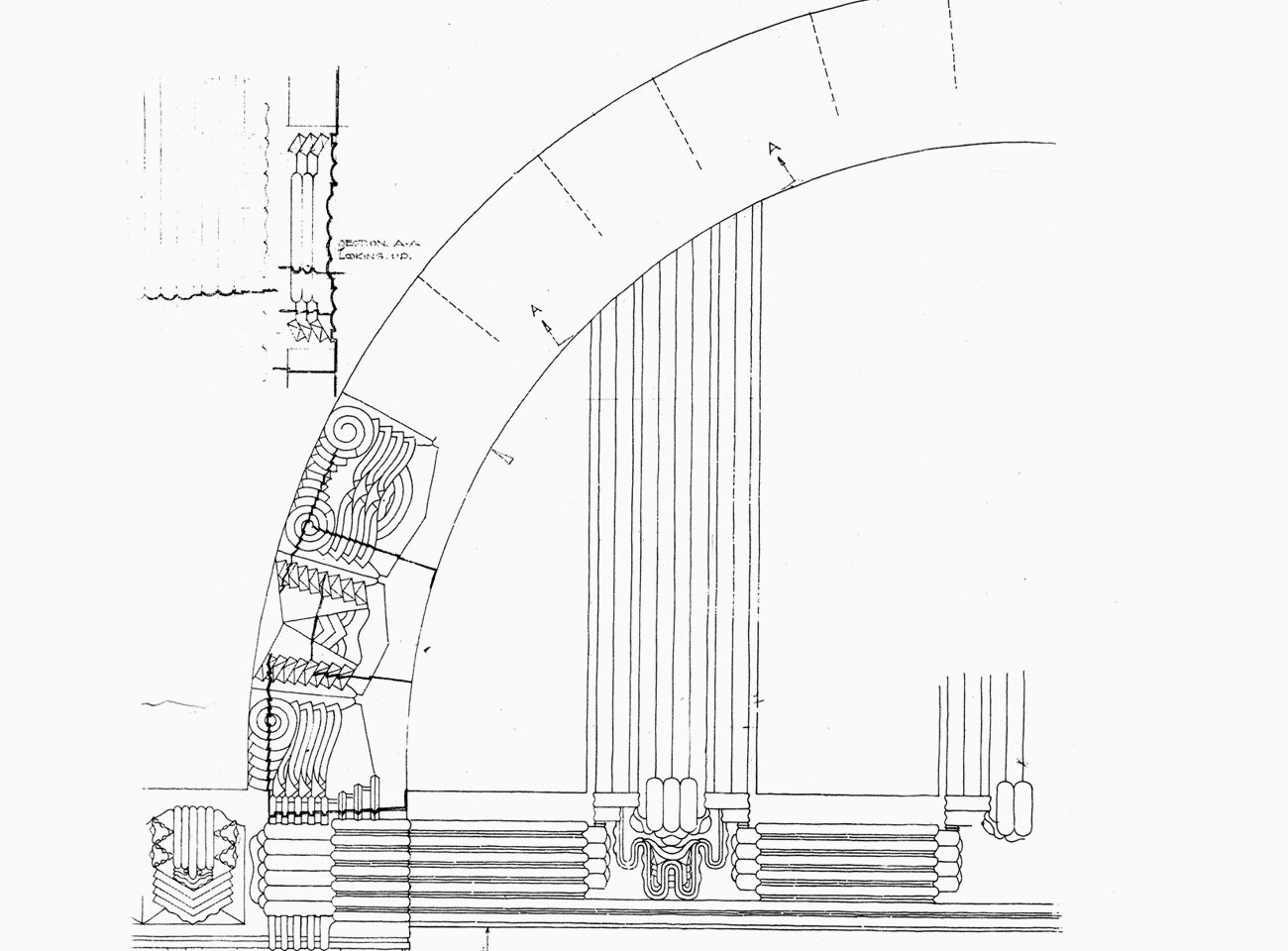

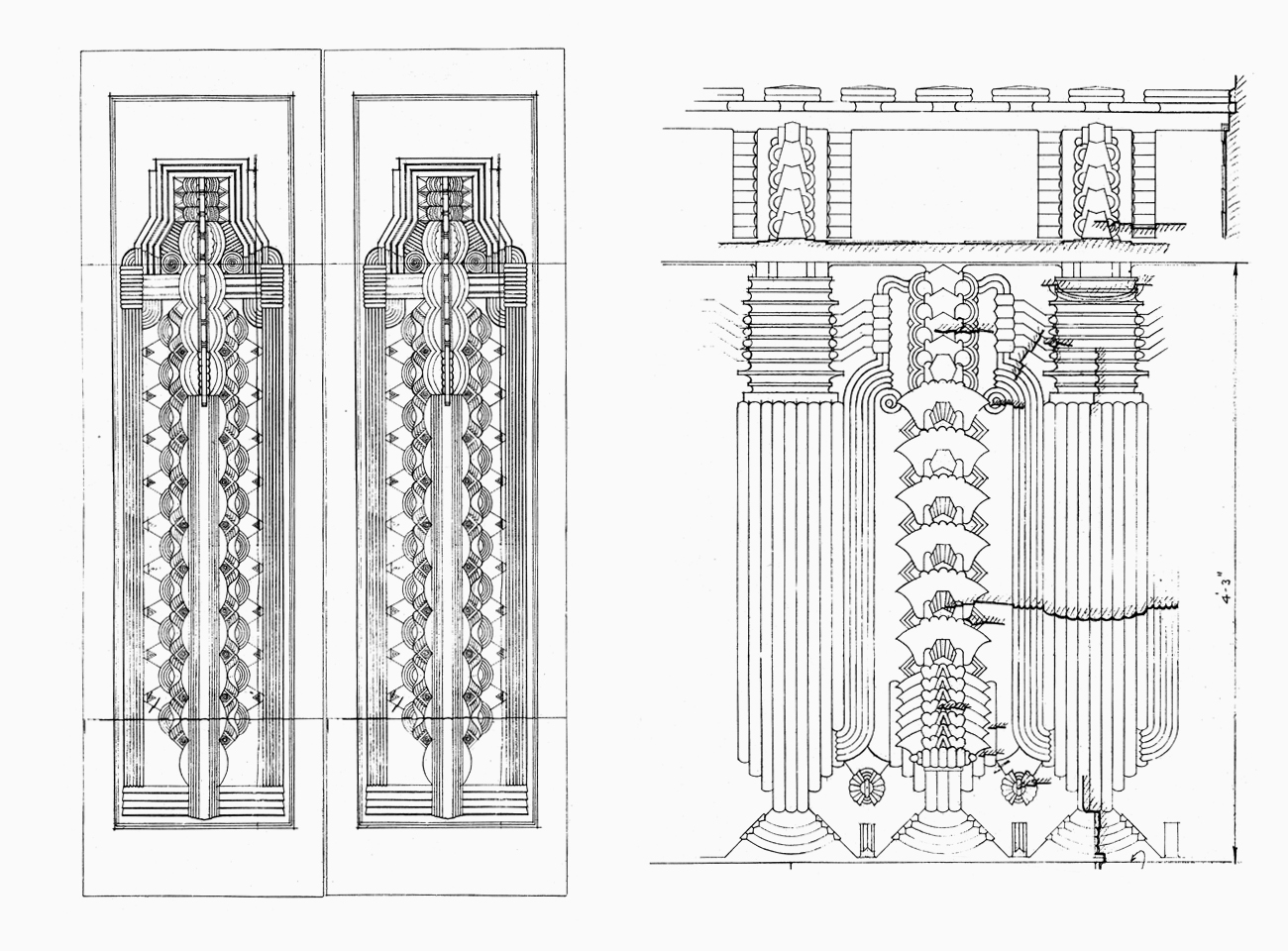

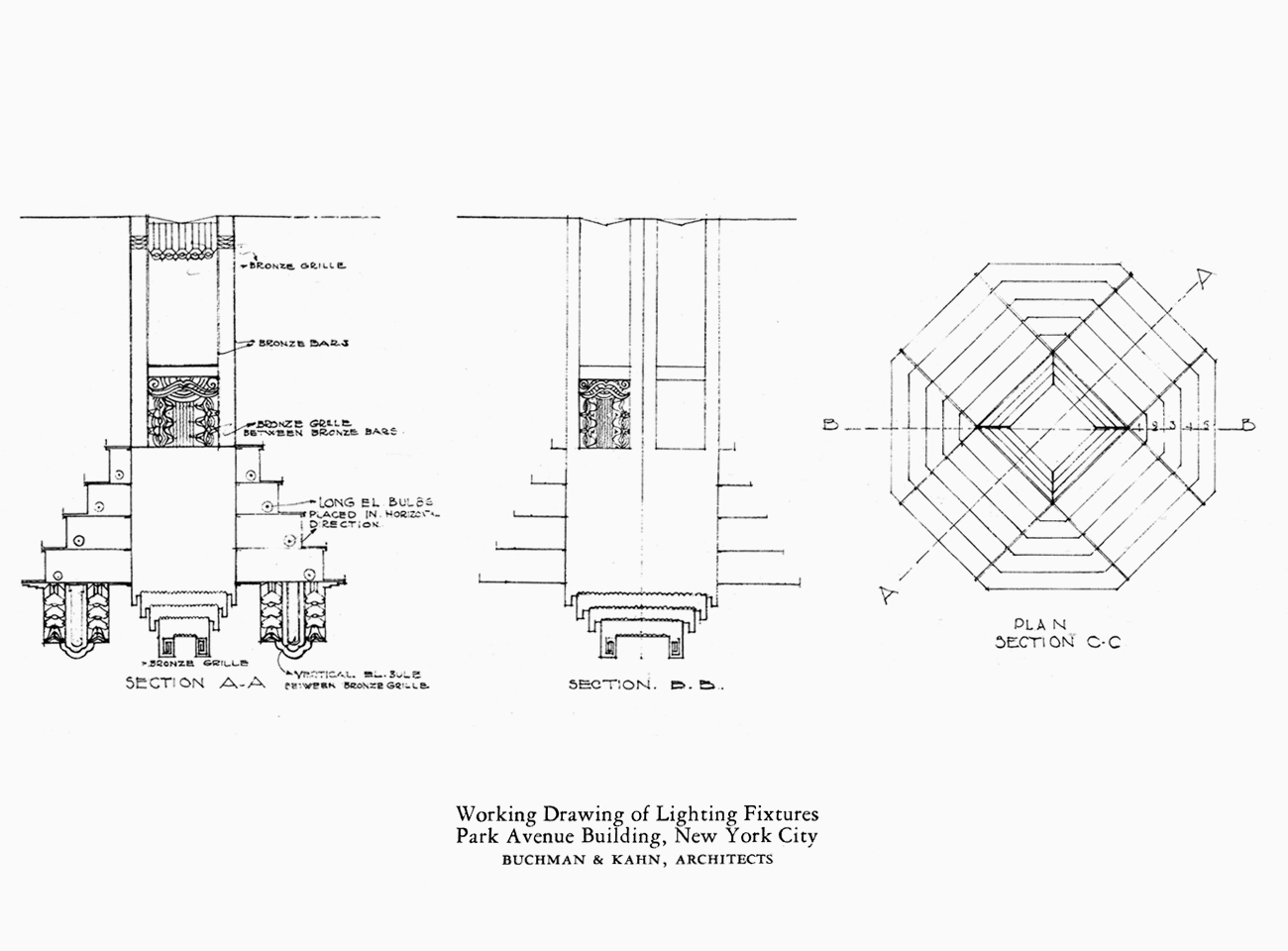

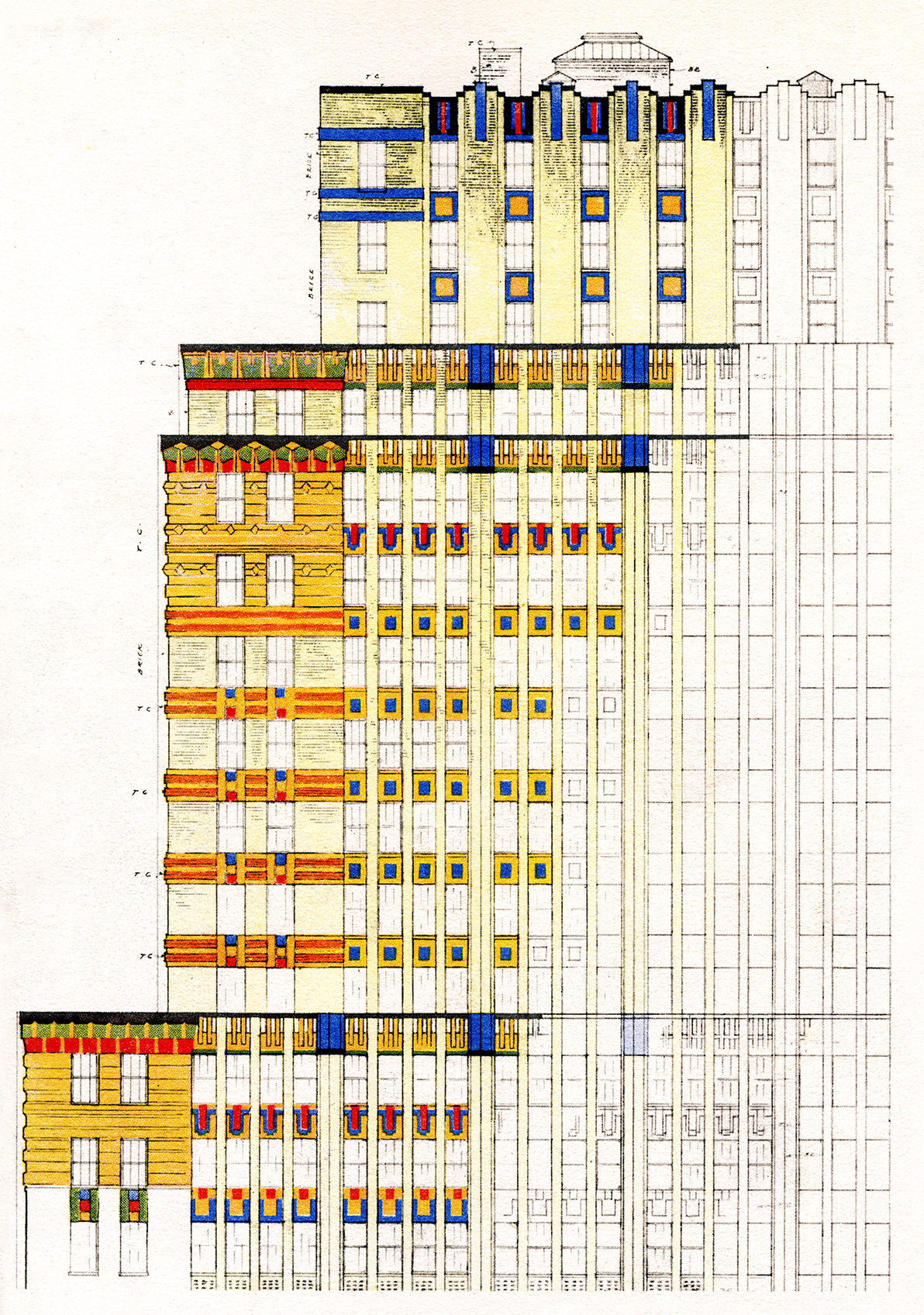

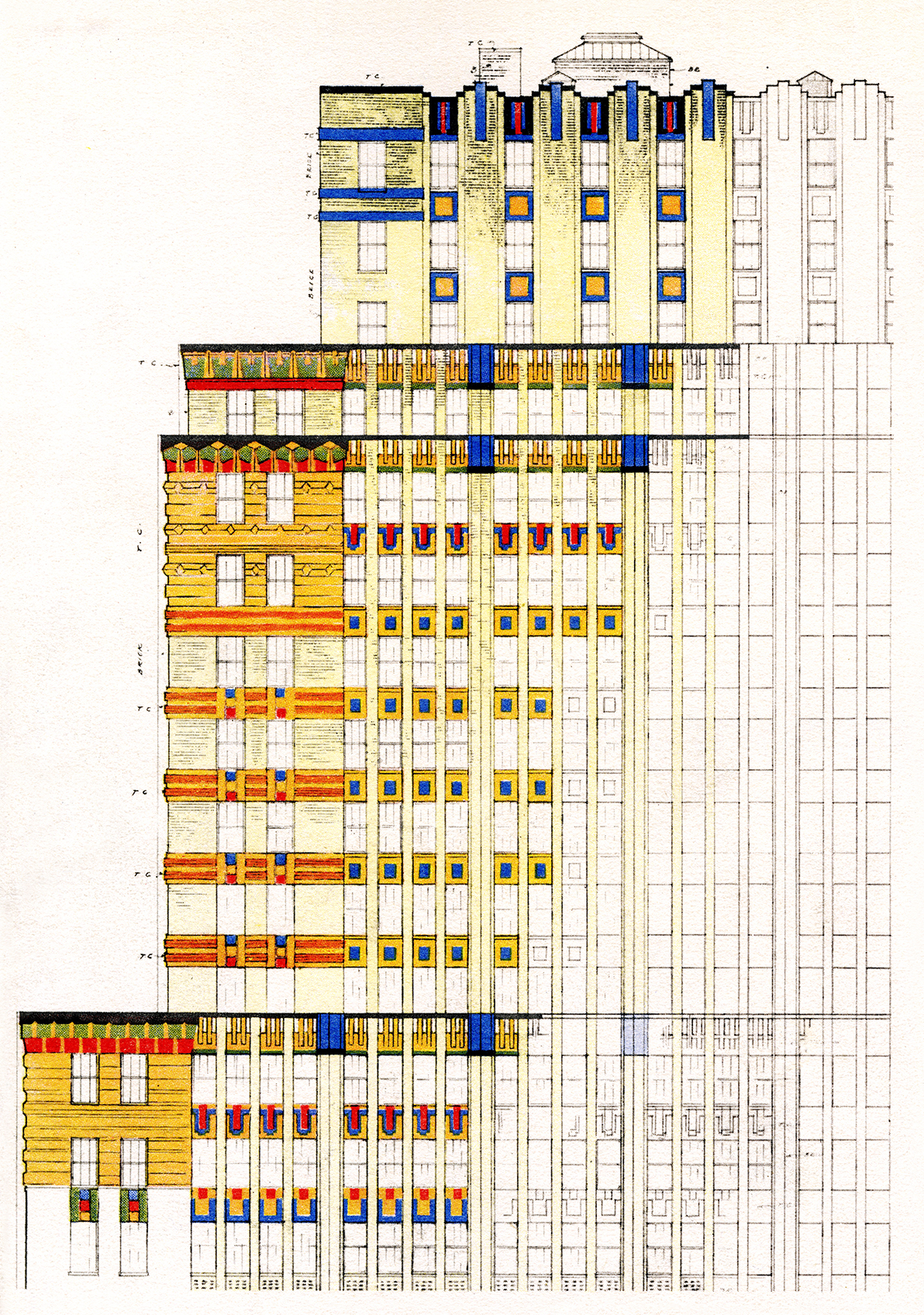

Detail drawings of Two Park Avenue’s interior and exterior, published in The Architectural Record v. 63, n. 4 (April 1928).

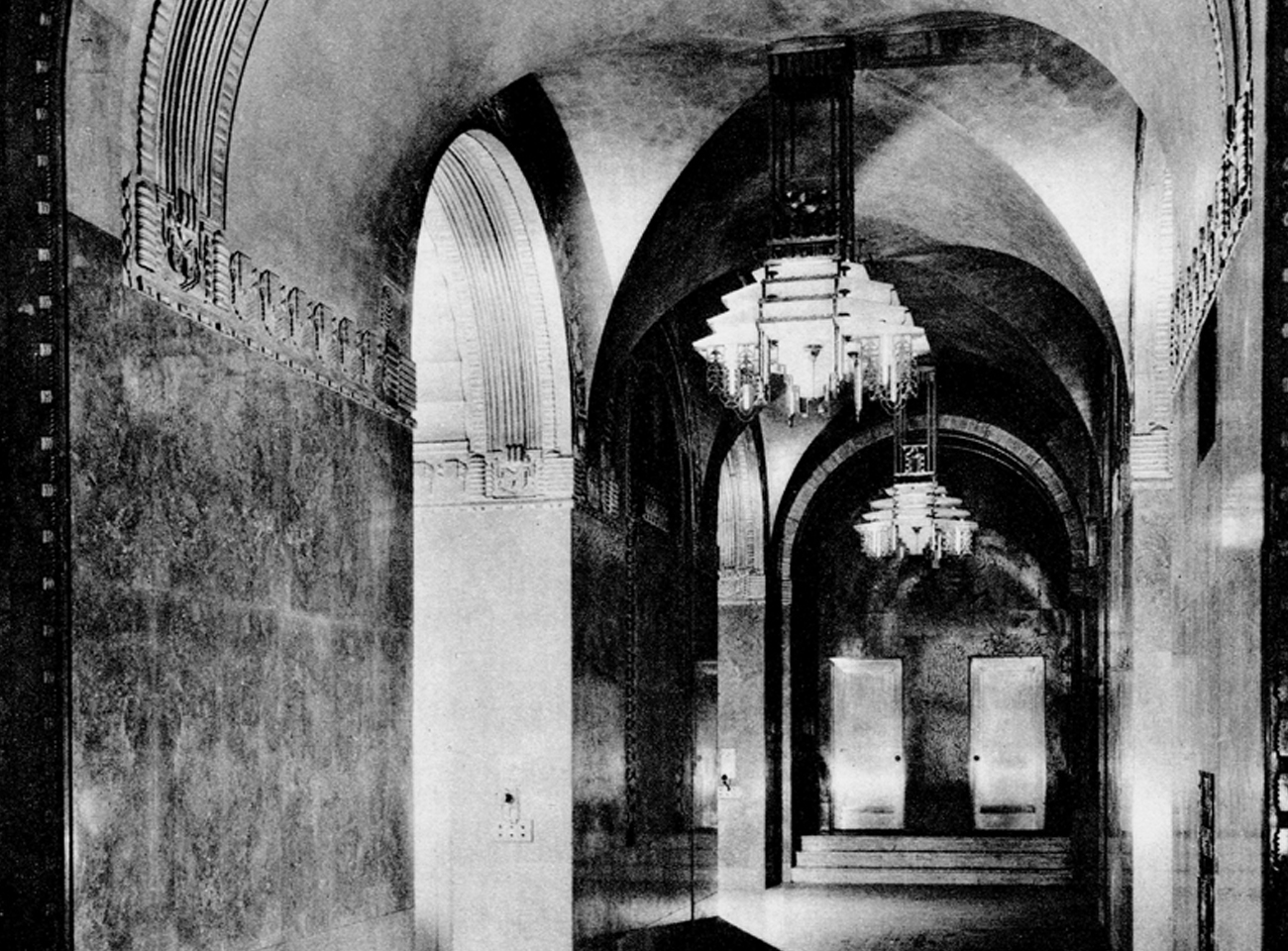

Detail photographs of Two Park Avenue’s interior and exterior, published in The Architectural Record v. 63, n. 4 (April 1928).

Although Two Park Avenue has only ever been in the background of my life, the building was in the foreground for Ayn Rand, who in 1937 and 1938 would pass under its glitzy geometric ceiling mosaic and through its ornate bronze revolving doors daily. Rand’s destination in the building was the top floor, where Buchman & Kahn had moved after the building was complete. It was in Two Park Avenue that Rand first went to work on her novel The Fountainhead (1943).

Ely Jacques Kahn and Rand had come to a curious arrangement: unknown to her colleagues, Rand offered to work as an unpaid typist in exchange for the opportunity to be among architects, which, as she explained to Kahn, would help her write a compelling novel about the profession. She joined colleagues for meals on the terrace, attended client meetings and lectures, discussed the profession, and discreetly jotted down gossip about Kahn’s contemporaries, including Raymond Hood, who “hated [Frank Lloyd] Wright for being what he, Hood, only appears to be.” [3] Rand leaned heavily on her undercover observations, even looking to Kahn as a model for a fictional counterpart in the melodrama: Guy Francon, a reputable and successful architect whose traditional designs, in Rand’s eyes, lacked modern innovation and the spark of individual genius.

The Fountainhead portrayed a profession marred by collective compromise in which architects self-sacrificed their ideals to the detriment of society. As an alternative, Rand turned to Frank Lloyd Wright, whose uncompromising design approach (and ego) made him a fitting archetype for her individualist philosophy and for the book’s principled, go-it-alone protagonist Howard Roark. By the time Rand’s book had made bestseller lists, Wright, perhaps seeing himself in Roark, praised her: “I’ve read every word of The Fountainhead. Your thesis is the great one. . . . So I suppose you will be set up in the marketplace and burned for a witch. Your grasp of the architectural ins and outs of a degenerate profession astonishes me.” [4]

Kahn, on the other hand, asked not to be specifically acknowledged for his role in shaping her views, perhaps worried about the controversy the book indeed ultimately stirred. So instead, Rand offered her profound “gratitude to the great profession of architecture and,” at Kahn’s request, to “its heroes who have given us some of the highest expressions of man’s genius, yet have remained unknown . . . .” [5] Where Rand saw the stifling of individual talent, as I see it, she failed to recognize the many architects, artists, craftspeople, and laborers—the unknown heroes—who bring a building into being. Two Park Avenue, which she intimately knew, is an exemplar of collective genius: Terra-cotta tiles glazed in red, black, ochre, cerulean, and teal were carefully developed at full-scale in coordination with color consultant and ceramicist Leon V. Solon, who Kahn had befriended at the Architectural League of New York. Those doors that Rand passed through were crafted by the atelier of sculptor Gaston Lachaise. The entrance mosaic is attributed to Hildreth Meière, whose work can be found around New York City from One Wall Street to Rockefeller Center. Even Rand’s idol Wright had been mythologized, for he had a talented fellowship of designers behind him—from Marion Mahony Griffin to Fay Jones and many more.

This color study was put together by ceramicist and color consultant Leon V. Solon, who knew Kahn from the Architectural League of New York, where both were quite active. It features in Solon’s essay “The Park Avenue Building, New York City: The Evolution of a Style,” The Architectural Record v. 63, n. 4 (April 1928).

Two Park Avenue stood out among its buff brick–colored neighbors of yesteryear, and today, it still radiates amid a monotonous backdrop of glass towers—a feat to be attributed to the many hands that played a role in shaping it. The building is a reminder that our own individual agency is most effective when tackling challenges collectively, to complement one another and accomplish what individual heroes alone cannot. With the end of the pandemic (and a return to our office) seemingly on the horizon, I am excited to once again have that daily reminder in the backdrop of my life, as I walk by on the street or catch glances of it out the window. And of course, I look forward to seeing familiar faces in the office.

Ornate bronzework and a vibrant ceiling mosaic greet visitors of Two Park Avenue. Photograph Leopoldo Villardi, 2017.

This essay grows out of an earlier piece written for The New York Review of Architecture in May 2020.

[1] The story of Cowdin, the wife of a former Secretary of State and ambassador to France Robert Bacon, is told in Andrew Alpern and Seymour Durst’s aptly named book Holdouts! (1984).

[2] Mumford wrote that Two Park Avenue “strikes the boldest and clearest note among our recent achievements in skyscraper architecture [and] shows the limits of the architect’s skill, to date, under urban conditions, where the program is inflexibly laid down.” Lewis Mumford, “American Architecture To-Day: Part I: The Search for Something More,” Architecture 57 (April 1928). Reprinted in Lewis Mumford, Architecture as a Home for Man, ed. Jeanne Davern (New York: Architectural Record, 1975).

[3] Rand recorded many observations about the profession in her manuscript notes, both in and out of Kahn’s office. In John Cushman Fistere, a writer at Vanity Fair, Rand saw a dismissive attitude that helped shape Ellsworth Toohey, a fictional architectural critic and the book’s arch-villain. Fistere dismissed Frank Lloyd Wright as “that aging individualist” who is more “genius than architect” in his “Poets in Steel” (1931), an essay that Rand knew. Fistere continues, “as an architectural theorist, Wright has no superior; but as an architect he has little to contribute for comparison.” Particularly insightful are Rand’s biographical interviews with Nathaniel Branden in the early 1960s. Courtesy the Ayn Rand Institute.

[4] Frank Lloyd Wright, letter to Ayn Rand (April 23, 1944). See The Letters of Ayn Rand, ed. Michael S. Berliner (New York: Penguin Group, 1995), 112.

[5] These are the words used in Rand’s acknowledgements at the beginning of The Fountainhead (1943).