The Scaffolding of an Architect’s Autobiography

Leopoldo Villardi

RAMSA Associate Leopoldo Villardi delves into the process of collaborating with Robert A. M. Stern on his new autobiography.

An architect’s buildings cannot be fully understood apart from the circumstances of the architect’s life. Few understand this better than Robert A. M. Stern, whose first significant piece of historical writing was a biography of an architect. For more than a decade, Stern pored over drawings and documents and interviewed associates of his subject. When he ultimately published George Howe: Toward a Modern American Architecture in 1975, Stern not only made a strong case for Howe’s significance in the canon of American architecture, but he also revealed the machinations of an architect’s personal life—the discontent of midlife malaise, the weight of taxing commissions, and Howe’s struggle to rechart the course of his career by reconciling traditional architecture with the technological demands of the present. Although buildings figure prominently in the legacies of those who create them, pivotal revelations, occasional contradictions, and personal hardships often make the architect.

Stern himself is no exception—his experiences register in his work as an architect, historian, and educator. But until recently, ambition and a near limitless work ethic have left little time for Stern to reflect on his own path. Encompassing elements of architectural history and culture, his recently published autobiography—Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture—surveys his life and seismic role in the field of architecture from the 1960s to the present.

Between Memory and Invention is the product of a long and varied collaboration. In early 2016, Patrick Corrigan, a designer at Robert A. M. Stern Architects, approached Stern with a proposal to conduct a series of oral history interviews. At the same time, Stern asked me to help him develop an academic seminar that focused on the emergence and decline of stylistic postmodernism. The seminar was broad—but given Stern’s own trajectory and intersection with key figures in architecture’s recent history, it was also in part autobiographical. Corrigan and I worked in parallel, often sharing research, and when he stepped away to focus on design, I continued the interviews. As Stern and I revisited some topics and touched on new ones, I became a witness to his irrepressible persona—bursts of wit, colorful characterizations, biting criticism, deeply held convictions, and a certain zeal for Golden Age Hollywood (all of which pepper the book’s pages).

As the interviews concluded, Stern asked me to help him chart a path forward. But Between Memory and Invention is by no means an as-told-to autobiography. Rather, it reflects a sincere, thoroughgoing effort by Stern to understand his own life and career. The oral history merely initiated an authentic process of discovery—the more one looked, the more details that emerged. Over a period of three years, Stern spent almost every weekend reviewing outlines, manuscript drafts, and supporting documents—a routine well known to those who have worked with him on writing projects. At the start of each new week with a freshly annotated stack of papers and notes in hand, the process of interviewing, researching, and re-writing began again. In my role as amanuensis, the goal was to maintain the historical record while also honoring Stern’s lived experience—an endlessly fascinating (and at times challenging) balancing act. I operated, in a way, as a kind of scaffolding to the process.

Robert A. M. Stern and Leopoldo Villardi. Photograph Bryan Coppede, 2017.

Writing about one’s own life (not to mention doing so collaboratively) is a challenging and time-consuming exercise—one must think in first person but also labor to think in third person, all while maintaining the patience to tease out meaning and to record those details that would be most interesting to readers. Memories invariably fade with time or are forgotten altogether. Furthermore, the single perspective privileged by an autobiography sometimes comes into conflict with the collective authorship of architecture. To help Stern through this process and recover lost details, I conducted additional interviews with his professional partners as well as former classmates, students, and colleagues. Many of these conversations are cited directly, offering a voice to some of the co-authors and collaborators whom Stern acknowledges as having important roles shaping his career and the firm’s architecture. Other interviews provided valuable context in structuring this book and complementing other forms of research.

Particularly helpful to early chapters in the book was the tranche of Stern’s professional papers and the firm’s project records gifted to the Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives in 2005. Records that have not yet been transferred to Yale and remain in the firm’s holdings in New York are cited as such. Together, Stern and I reviewed personal and professional correspondence, office call logs, appointment books, project sheets, architectural drawings, photographic slides, previous writings and interviews, contemporaneous notes, and a set of personal diaries. Although Between Memory and Invention is not a comprehensive catalog of work (for that, the reader can turn to any of the twenty-one chronologically and thematically organized monographs that have been published since 1981, each with detailed credits), our approach was nonetheless exhaustive, leaving an expansive atlas of the archival collection in the book’s footnotes.

The Robert A. M. Stern Architects Records collection at Yale University Library Manuscripts & Archives includes documents and drawings. Pictured is a plan of the Stern Apartment II.

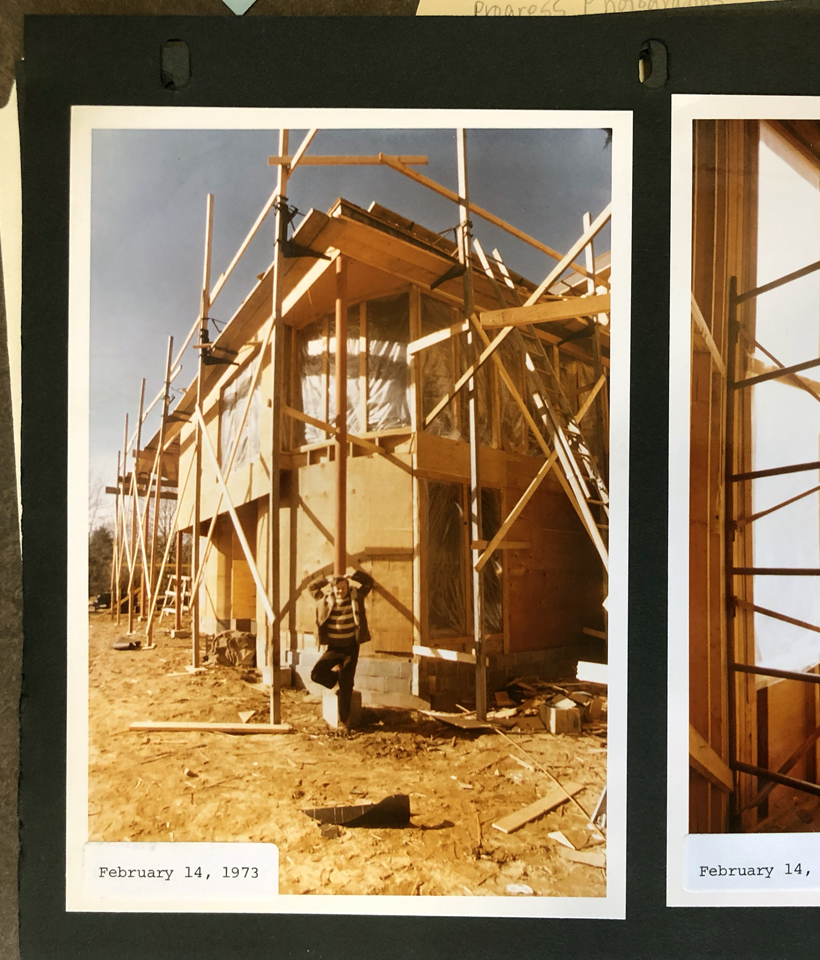

The collection includes many photographs and slides as well. Pictured are slides of the Lang House and a photograph of John Hagmann at the construction site of the Mercer House.

By turns thoughtful and irreverent, Between Memory and Invention is a candid account of a life in architecture. Stern’s struggles to launch an architecture practice in the 1970s amid a recession took a toll on personal and professional relationships. His deep commitment to the architectural and urban history of New York, which continues to this day with the forthcoming New York 2020, can be traced back to youthful efforts to redraw house plans in real estate ads and an adolescent affection for collecting New York–themed ephemera. Readers are given insight into the myriad ways commissions have come to the firm—from elevator encounters to good old-fashioned hustle (of which Stern still has a lot)—as well as Stern’s own midcareer transformation from Yale-trained modernist, to postmodernist, to self-taught traditionalist through hands-on design and research.

Importantly, Stern acknowledges those who helped put the firm on a sturdy foundation, notably John Hagmann, with whom Stern co-founded Stern & Hagmann Architects, and the late Rob Buford, who oversaw the firm’s growth at a critical time in its evolution. But Between Memory and Invention also looks to the future, previewing the next generation of leaders taking the reins at RAMSA. “The notion that a solitary architect works alone by private strokes of genius is, in my view, a foolish one—and it is not how I have operated over the years,” writes Stern. “I always prefer to work collaboratively.” Stern has cultivated a talented team of partners, each with compelling origin stories of their own—he recognizes that his legacy and the firm’s continued success rely on their ability to continue enriching the design tenets that he has instilled.

Over the last fifty years, Robert A. M. Stern has combined professional practice and historical research without straying far from the exigencies of running an office, revitalizing an organization, or leading a school. Stern has dedicated his life to a search for the usable past—as he sees it, sifting through architecture’s history will yield time-tested models ripe for future adaptation and better prepares architects to be benevolent stewards of our shared public sphere. Just as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard recalls her past as a silent film star, when “we didn’t need dialogue—we had faces,” Stern, too, would argue that buildings ought to have character and speak volumes on their own. And their facades, like the silent faces, also reveal the people behind their making—both as they are and as one might want them to be.

- Robert A. M. Stern with Paul Rudolph and fellow students. From left: Paul Rudolph, Edward T. Groder, M. J. Long, Robert A. M. Stern. Photograph Elliott Erwitt, 1962. Courtesy Magnum Photos.

- Robert A. M. Stern and J. Max Bond during the filming of Pride of Place. Photograph Mobil Masterpiece Theater, 1985.

- Site model of Yale University’s campus and Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin Colleges. From left: George de Brigard, Robert A. M. Stern, Melissa DelVecchio, and Milton Hernandez. Photograph 2008.

- Feature Animation Building team. From left: Barry Rice, Paul Whalen, Robert A. M. Stern, Michael Jones, and Geoffrey Mouen. Photograph 1992.

- Robert A. M. Stern and Philip Johnson at the Glass House. Photograph Mobil Masterpiece Theater, 1985.

Cover of Between Memory and Invention. Photograph Peter Jakubowski, 2021.

An earlier version of this essay appears as the afterword to Between Memory and Invention. The book was designed by Michael Bierut and Jena Sher, and published by the Monacelli Press.

To purchase a copy, visit the Monacelli website.