Five Moments That Transformed NYC Real Estate Between 2000–2020

David Fishman

Jacob Tilove

Along with Robert A.M. Stern, we had the challenge and privilege of authoring New York 2020: Architecture and Urbanism at the Beginning of a New Century, but frankly, we never thought the book would be written.

In 2006, when we completed New York 2000 as the fifth volume in the New York series, we thought it would be the final installment. Instead, the many remarkable events of the past twenty-five years so fundamentally reshaped New York design and real estate that we felt compelled to continue the story with New York 2020.

In this exhaustive 1,500-page book, we dive deep into the local and global events that propelled a twenty-year rollercoaster ride of economic ups and downs, urban development, architectural experiments, and cultural shifts, culminating in the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, five uniquely historic moments stand out for their outsize impact on the first two decades of the 21st century in New York—we've highlighted each below.

Ground Zero under construction. Photograph: May 20, 2006.

September 11, 2001

The attacks of September 11, 2001, triggered a sudden and monumental shift in New York City’s real estate and architectural landscape. Before that day, “everything seemed to be going right,” as New York Times reporter Adam Nagourney observed; in contrast to many parts of the nation, the city’s economy and real estate market were thriving.

Of course, this changed in an instant. Beyond the devastating loss of life, more than 26 million square feet of prime Lower Manhattan office space vanished—12.5 million destroyed outright and another 14 million severely damaged. The destruction of the Twin Towers even raised existential questions about the future of skyscrapers themselves, as these proud symbols of ambition and progress were suddenly perceived as vulnerable targets for terror.

In the years that followed, massive public and private investment—totaling more than $20 billion—transformed the 16-acre site and revitalized Lower Manhattan. The new buildings at 1, 3, 4, and 7 World Trade Center restored over nine million square feet of Class A office space, while the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, Santiago Calatrava’s Oculus, the Perelman Performing Arts Center, and 365,000 square feet of new retail added cultural and public space dimensions. Since 2001, the neighborhood’s residential population has doubled, tourism rebounded, and the skyline stands as a global symbol of New York’s capacity to adapt, rebuild, and thrive in the face of profound loss.

View looking south to Hudson Yards (right) and Manhattan West (left). Photograph: Connie Zhou, 2019.

The Great Recession

Beginning in late 2007, New York City’s economy plunged into crisis as the Great Recession took hold—the most severe financial downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Triggered by the collapse of the national housing bubble and the implosion of mortgage-backed securities, the crisis devastated financial institutions and wiped out more than half of the stock market’s value in just six months. As the epicenter of global finance, New York felt the full weight of the collapse, prompting former city economist John Tepper Marlin to call it a bigger economic challenge than September 11.

The real estate sector was among the hardest hit. Financing for major developments dried up, construction costs soared, and investor confidence evaporated. Within months, the Department of Buildings reported nearly a 50 percent drop in new permits, and by mid-2009, over 400 construction projects were officially classified as “stalled,” including high-profile megaprojects like Hudson Yards and Atlantic Yards.

Although New York City was more adversely affected by the recession than other parts of the country, its recovery turned out to be significantly quicker, aided in large part by the federal government’s extensive and controversial bailout of Wall Street’s largest financial institutions. By 2011, unemployment fell, tax revenues rose, and long-delayed projects came back to life. Major development work at Hudson Yards, Long Island City, and the World Trade Center site resumed, along with a continued boom in luxury residential towers—including RAMSA’s record-setting 15 Central Park West.

The flooded Battery Park Underpass on October 30, 2012, in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Photograph: Patrick McFall.

Superstorm Sandy

Superstorm Sandy, which struck New York City on October 29, 2012, permanently altered the conversation around urban resilience, real estate, and waterfront design. A year prior, the city had narrowly missed devastating impacts from Hurricane Irene. A New York Times front-page story cautioned that New York was “moving too slowly to address the potential for flooding,” and just six weeks later, Sandy delivered two massive storm surges that swamped the city. The result was catastrophic: 43 deaths, 51 square miles flooded, 90,000 buildings damaged, and 800 destroyed or structurally compromised. The storm inundated subways, knocked out power for millions, and exposed just how vulnerable the city’s coastal infrastructure truly was.

The response from all levels of government was both immediate and far-reaching. FEMA redrew its flood maps, doubling the number of residents expected to live in flood zones by 2050. The city’s Build It Back program funded home repairs and reconstructions, while the state pursued “managed retreat,” purchasing hundreds of flood-prone homes on Staten Island’s shore and integrating the land into the Mid-Island Bluebelt of parks and wetlands. Simultaneously, the city overhauled its building codes and planning frameworks. Mayor Bloomberg’s Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency proposed 250 measures—from deployable flood barriers and levees to oyster reefs and restored wetlands—while President Obama’s Rebuild by Design competition invited innovative coastal infrastructure concepts across the metropolitan region.

Superstorm Sandy fundamentally changed New York’s relationship with the built environment. No longer could the city treat rising seas and severe storms as distant threats. The rebuilding efforts following Sandy positioned resilience as a central tenet of urban design—infusing it into zoning, infrastructure, architecture, and public space planning alike. From Lower Manhattan’s coastal defenses to resilient housing prototypes in the Rockaways, the legacy of Sandy endures as both a warning and a blueprint for a more resilient future.

Aerial view of Phase II of the Hunters Point South Waterfront Park. Photograph: SWA/Balsley and Weiss/Manfredi, 2018.

Large-Scale Rezoning

Between 2000 and 2020, New York City used zoning to reshape entire neighborhoods—converting former industrial areas into vibrant mixed-use districts and directing growth around transit hubs.

Early changes in the outer boroughs set the tone. The 2001 Long Island City rezoning encouraged new residential and commercial development around Queens Plaza and Court Square and paved the way for waterfront projects like Hunters Point South. In 2004, the Downtown Brooklyn Plan unlocked major housing and office growth, while the 2005 Greenpoint–Williamsburg waterfront rezoning opened the door to high-rise housing tied to affordable-housing incentives, transforming the Brooklyn waterfront into one of the city’s most desirable areas.

On Manhattan’s West Side, the 2005 Hudson Yards and West Chelsea rezonings were especially significant. Hudson Yards created the framework for an entirely new business district with millions of square feet of office, housing, and retail space. West Chelsea enabled the adaptive reuse of the High Line, which became the spine of a design-focused residential and arts neighborhood stretching into the Meatpacking District. In later years, rezonings in Hudson Square, East Midtown, and Inwood fine-tuned this growth model, pairing new density with public improvements and affordable housing. Together, these efforts—along with the 2016 adoption of Mandatory Inclusionary Housing—shifted vast areas of the city toward higher-density mixed-use development, helping to shape the skyline and urban fabric of New York today.

View looking southeast from Columbus Circle of the tall and supertall towers along Central Park South. Photograph: Francis Dzikowski.

The Rise of the Supertalls

The 2010s in New York City were dominated by an unprecedented wave of supertall construction that reshaped the skyline and redefined urban luxury. The trend was driven by a convergence of factors: a strong post-recession economy, surging global investment in real estate, and advances in engineering and materials that made ultra-slim towers both feasible and profitable. As demand grew for high-end residential and office space, developers seized on Manhattan’s limited supply of land and its iconic skyline as an opportunity to build further upward than ever before.

One World Trade Center, completed in 2014, reasserted Lower Manhattan’s vertical dominance, but it was “Billionaires’ Row” along 57th Street—towers like One57, 432 Park Avenue, 111 West 57th Street, and Central Park Tower—that exemplified the era of super-slender, ultra-luxury residential buildings. Their narrow silhouettes transformed the city’s skyline and real estate market, where single apartments could fetch prices exceeding $100 million.

The boom’s influence extended beyond Midtown. Developments at Hudson Yards, Manhattan West, and Downtown Brooklyn demonstrated how supertalls could anchor entire mixed-use districts. Critics have questioned their social and environmental implications, but their impact on the city’s real estate and architectural character is undeniable.

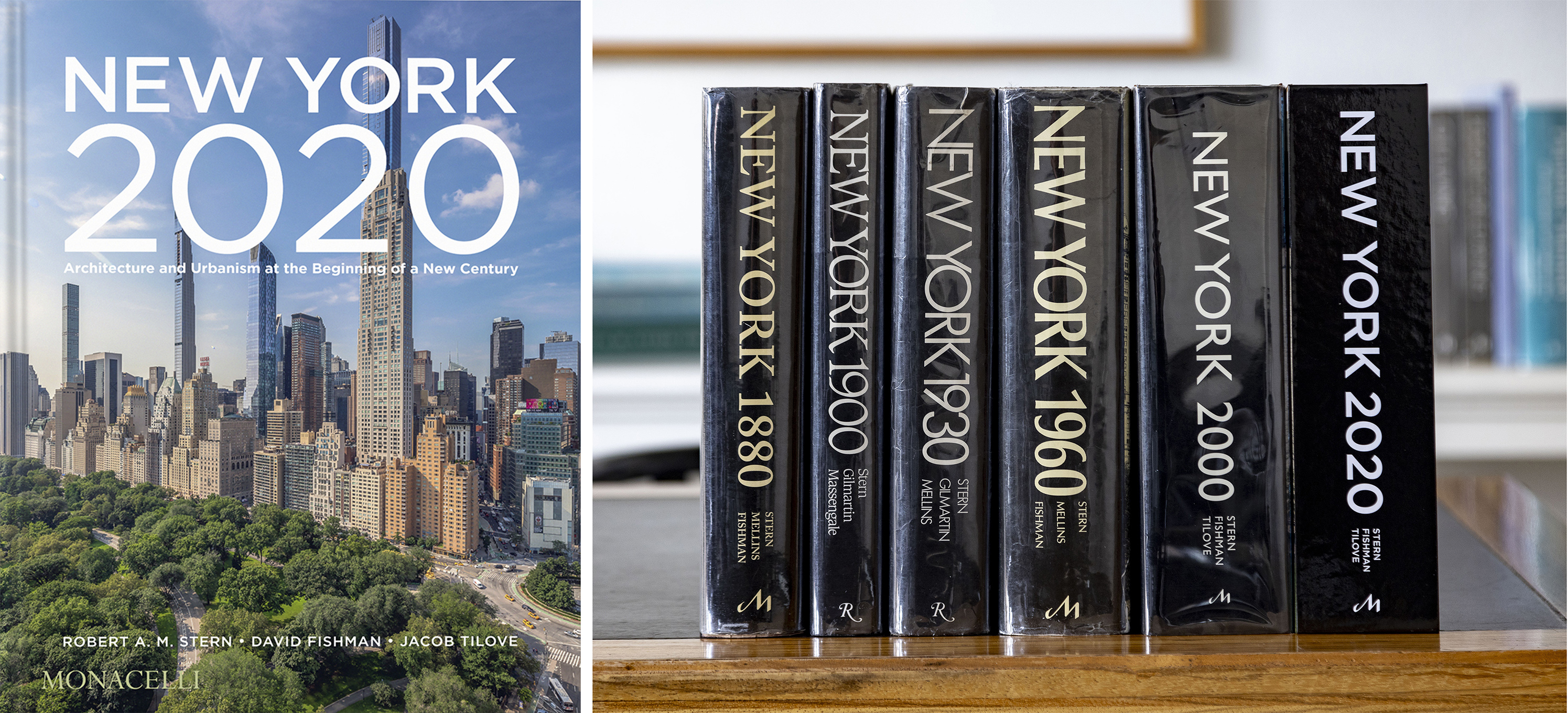

Left: New York 2020 (Monacelli, 2025). Right: the complete New York book series—New York 1880 (Monacelli, 1999), New York 1900 (Rizzoli, 1992), New York 1930 (Rizzoli, 1987), New York 1960 (Monacelli, 1997), New York 2000 (Monacelli, 2006), and New York 2020.

New York 2020

These five events dramatically reshaped the city, but each is just one part of a larger story. Click here to learn more about New York 2020 and this remarkable period in the city's history.

David Fishman is a coauthor of New York 1880, New York 1960, New York 2000, New York 2020, and Paradise Planned.

Jacob Tilove is a coauthor of New York 2000, New York 2020, and Paradise Planned.