A Discussion About Travel, Research & the RAMSA Fellowship

RAMSA Fellowship Jury and RAMSA Research

RAMSA Partners Melissa DelVecchio, Dan Lobitz, and Grant Marani discuss the RAMSA Fellowship, a $15,000 prize awarded annually to graduate students for travel and research.

RAMSA Research: We thought we would start with the origins of the RAMSA Fellowship. Can you tell us how the program started?

Melissa DelVecchio: When we launched the fellowship in 2013, we were thinking about ways that we could give back to the profession and engage with current students, to learn what they are doing and what they are thinking about in their classes. In a way the fellowship is an extension of Bob Stern’s teachings at Columbia and Yale. He has always encouraged his students to experience buildings and their contexts in person, and that kind of research is central to the way we approach our design work at RAMSA.

RR: You touched on the importance of seeing architecture firsthand. What is the value of travel to the architecture discipline?

Grant F. Marani: Melissa, Dan, and I are all from a generation of architects who looked at photos and slides to understand buildings. This is an imperfect substitute for the experience afforded by seeing architecture firsthand since every building has a particular scale in relation to its specific context. By being on the street, looking at a building and seeing it in context, you get a sense of the architect’s original intentions and how it has evolved over time. Today’s students browse the Internet. With the wealth of information accessible online, there is a tendency to think that you can get a full impression of a place using digital tools alone, but we disagree. We are still struck by how different it is to visit a place in person, and we hope young architects do not settle into the feeling that traveling to real places is less necessary than it used to be. Travel has always been, and still is, extremely important to architects and to the discipline of architecture.

Watercolor of Holmwood House, Cathcart, Scotland (Alexander Thomson, 1858). Drawing Gerald Bauer, 2016.

MD: My college professor, Dennis Doordan, used to say in almost every lecture, “Photographs always, always, always lie.” And he’s right! So many times I’ve visited a building or a place and realized that it’s nothing like the picture—there are always surprises. On my first trip to Beijing I was absolutely blown away by the size and scale of the places, especially the Great Hall of the People. I remember telling my parents, “It’s crazy—almost every building in Beijing is the size of the Javits Center!” A week later I drove by the Javits Center and thought, “Wow, I’m totally wrong. The buildings in Beijing are much bigger than the Javits Center!” I’m a real sucker for scale comparisons now. I’ve learned from living in Rome as a student and visiting other places that your perception is as much related to scale as it is to details. I’m always taking pieces of one building and laying them over another in plan and elevation, or comparing a design to some other building. This is one example of what you get from travel: an appreciation for all aspects of design. It’s not just about a sense of place but how scale can contribute to that and how it all works together to create an impression.

Daniel Lobitz: As architects we are constantly designing projects on sites in different cities, sometimes in places we’ve never visited before. How do you absorb the details of a particular place in such a way that you can design an appropriate response to the situation? I just started work on a project in Brooklyn and was on-site yesterday for a meeting. I’ve been there before, and we’ve done preliminary background research using aerial photos and Google Earth, but after the meeting we spent an hour walking around the neighborhood and photographing the building site from different perspectives. It’s the middle of winter, yet the streets were full of life: people sitting on their stoops petting their dogs or reading books, or strolling along. It’s the kind of thing that on paper you recognize as “Oh yes, this elevation faces west and has nice exposure,” but being there and seeing life interact with architecture makes a big difference.

Kyle Schumann takes a foam impression of a concave ceramic tile on a masonry heater in a villa at Villaggio ENI Colonia (Edoardo Gellner, 1955−62) in Corte di Cadore, Italy. Photograph 2017.

Jonathan Dessi-Olive tests the strength of a small groin vault mockup at PennDesign in Philadelphia in preparation for his fellowship trip. Photograph 2013.

RR: Architecture is a three-dimensional medium and, as you mention, photographs can be deceiving. So, how are the fellowship proposals, which include two-dimensional imagery, judged?

DL: Yes, this is certainly a challenge for us as jurors. Proposals of past fellows stood out for their clarity, originality, responsiveness to the prompt, significance to the profession, and thoughtfully considered itineraries. Applicants are also required to submit a portfolio, and we find that the strongest research projects are often part of a larger, sustained commitment to a particular idea that has also been explored in coursework and through design concepts. The theme—tradition and invention—allows for a broad range of topics and locations, so the fellows’ interests really drive the projects. That’s another reason why travel fellowships are important to architecture students—they offer an opportunity to complete in-depth research on a self-directed topic.

RR: The fellowship is open to graduate students in their penultimate year of architecture school. Why is it valuable for fellows to complete the travel and research before their final year in school?

MD: We do this so that their research benefits their classmates and professors too. When fellows return to school in the fall, in effect, their travel also becomes a resource for their coursework and future projects.

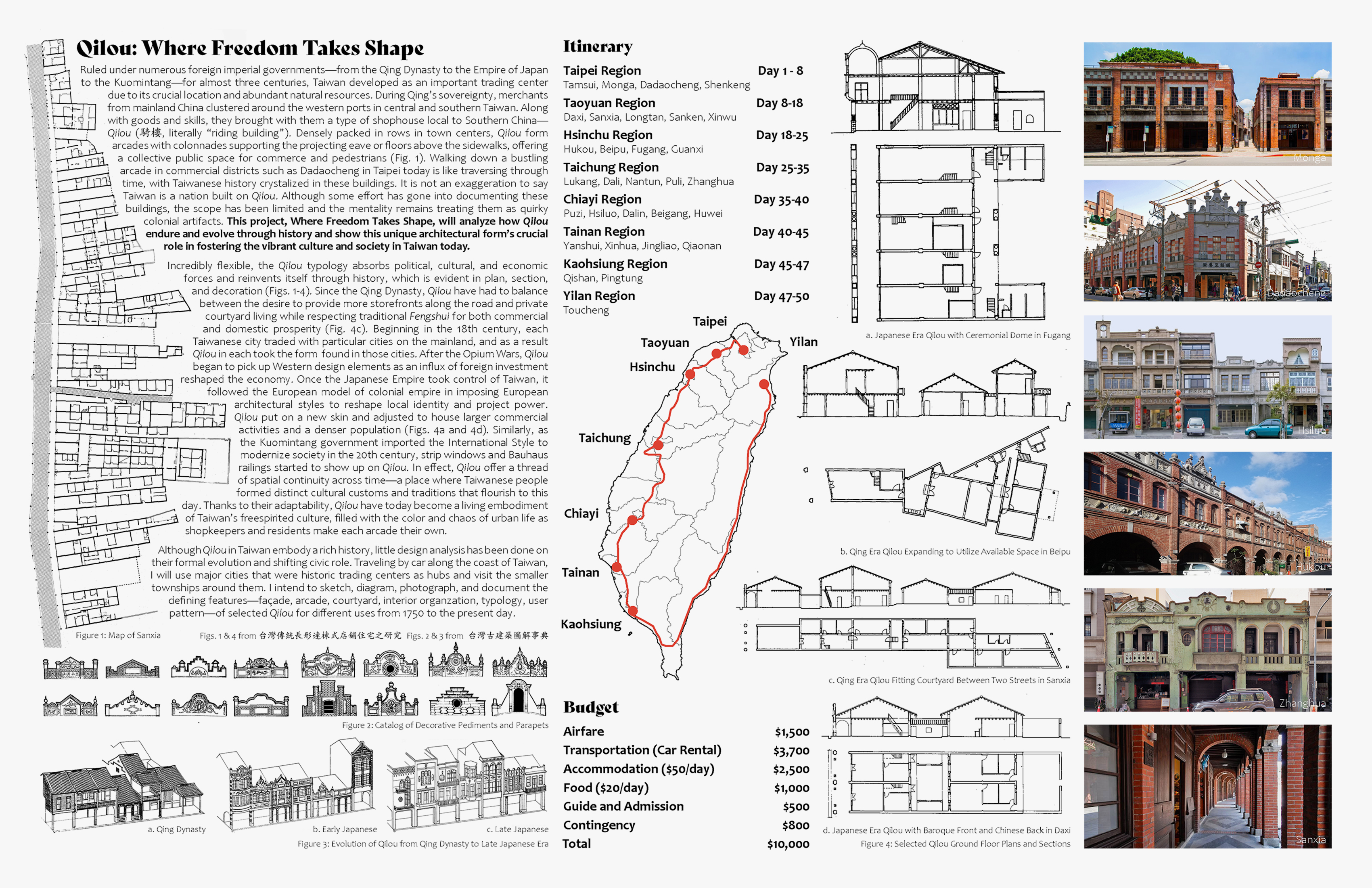

Yaxuan Liu’s winning proposal to study and document the historic Qilou building type along the west coast of Taiwan, 2020 RAMSA Fellowship.

An excerpt from Daniel Hall’s portfolio submission to the 2021 RAMSA Fellowship. Hall will travel to Japan to study the architecture and traditional crafts of the Ryōan-ji, a house located in Kyoto and built in 1450. Following an analysis of the house, Daniel will trace the material productions that contribute to its final form by studying metalwork in Yamagata, tatami weaving in Saitama, papermaking in Echizen, indigo dyeing in Aizumi, and ceramics in Arita and Imari. His portfolio supported his research interest of in-depth material studies.

RR: We imagine that this was informed by some of your own experiences. What was the first trip you took as an architecture student or simply with the intention of studying buildings?

DL: My first significant trip as an architecture student at Columbia was to Rome and other parts of Italy. Funded by the William Kinne Fellows Traveling Prize, it allowed me the opportunity to experience firsthand what I had learned in school. Rome is a touchstone for so many architects, and to see the city for the first time—after having the benefit of training, knowing what was there, and piecing together how the architecture of the place had developed over the course of centuries—was an eye-opening experience.

MD: I grew up in suburban Connecticut, so Yale University and New Haven were my first encounters with great architecture and any kind of urbanism. Yet the most influential travel for me was my year studying abroad in Rome as an architecture student at Notre Dame. The experience of living in a city for the first time was almost as important as the buildings that I saw.

Melissa DelVecchio (front, left) at the Temple of Hera or Juno Lacinia in Agrigento, Sicily, Italy (c. 450 BCE). Photograph 1992.

Daniel Lobitz at the Palazzo Zuccari (Federico Zuccari, c. 1590–1610) Rome, Italy. Photograph 1985.

GM: Sometimes you don’t have to travel far to see great architecture. There are many great buildings here in the United States, and we’ve had applicants propose trips to places around the country. When I was a graduate student at Cornell University in the early 1980s, I received the Eidlitz Fellowship to study the work of Louis Sullivan in the Midwest. I traveled to Chicago and many small Midwestern cities and towns where he designed numerous beautiful jewel-box banks. I was new to the States—I am originally from Australia—and at the time I had never been to the Great Plains or the Midwest. The fellowship gave me the opportunity to travel, just as ours offers students an opportunity to do research and travel to places that would otherwise be out of reach.

RR: Can you share a specific example of a location or building that influenced your work as a student or an architect?

MD: I find myself reflecting on two of my favorite buildings, both in Rome—the Tempietto and Trajan’s Market. I think of them as different ends of a spectrum of what architecture could be: the Tempietto is a perfectly proportioned singular object, and Trajan’s Market is a complex combination of urbanism, landscape, and architecture that is indistinguishable from the building form because it is so closely intertwined with its context. Architecture and urbanism are often taught as two separate disciplines, but through travel you understand how these two aspects work hand in hand, particularly in a great city, or even a great single building.

GM: Until recently architecture students in Australia were required to “take a break” between the third and fourth years of their undergraduate professional degree. During my break I went on a walkabout, as we say, to several countries in Asia. I started in Singapore, traveled through Malaysia and Thailand, and then spent about a month in India, finishing my trip in Sri Lanka. While in India I was fascinated by stepwell architecture—it was unlike anything I had seen. The idea of inhabiting many stories below grade to collect water astounded me. I was fortunate to visit traditional cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, and Varanasi and new cities like Chandigarh, allowing me to experience the differences between the messy vitality of the former and the dull urbanism of heroic object buildings in the latter. For me the invigorating liveliness of the older cities, despite their many problems, was preferable to the absolute finality of “nowhere” in Chandigarh. That realization was a formative moment.

Grant Marani at Chandigarh, India (master plan and buildings Le Corbusier, 1950–65). Photograph 1976.

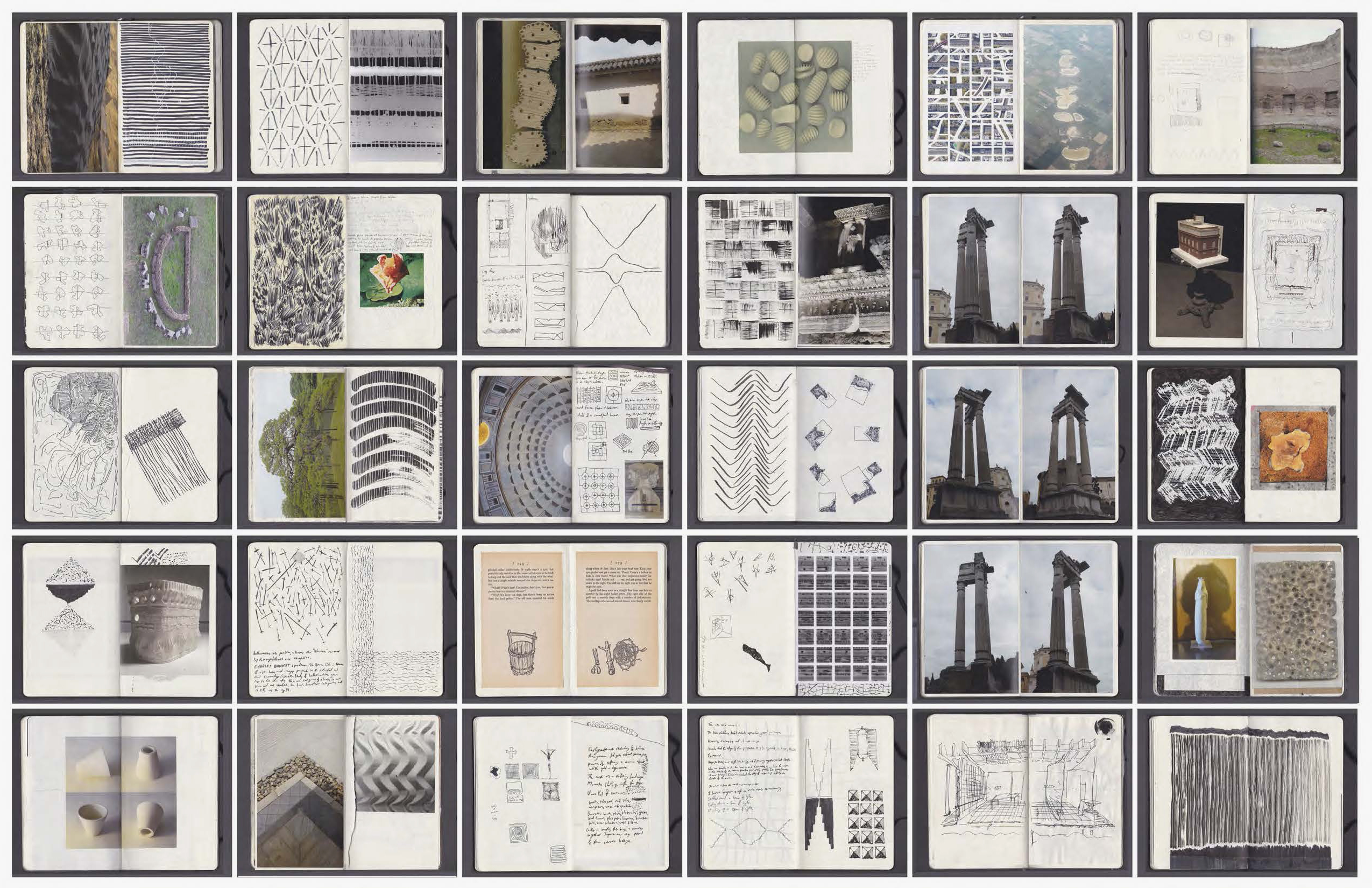

RR: We know that Bob prefers photography to drawing when he travels. What is the product of your own trips?

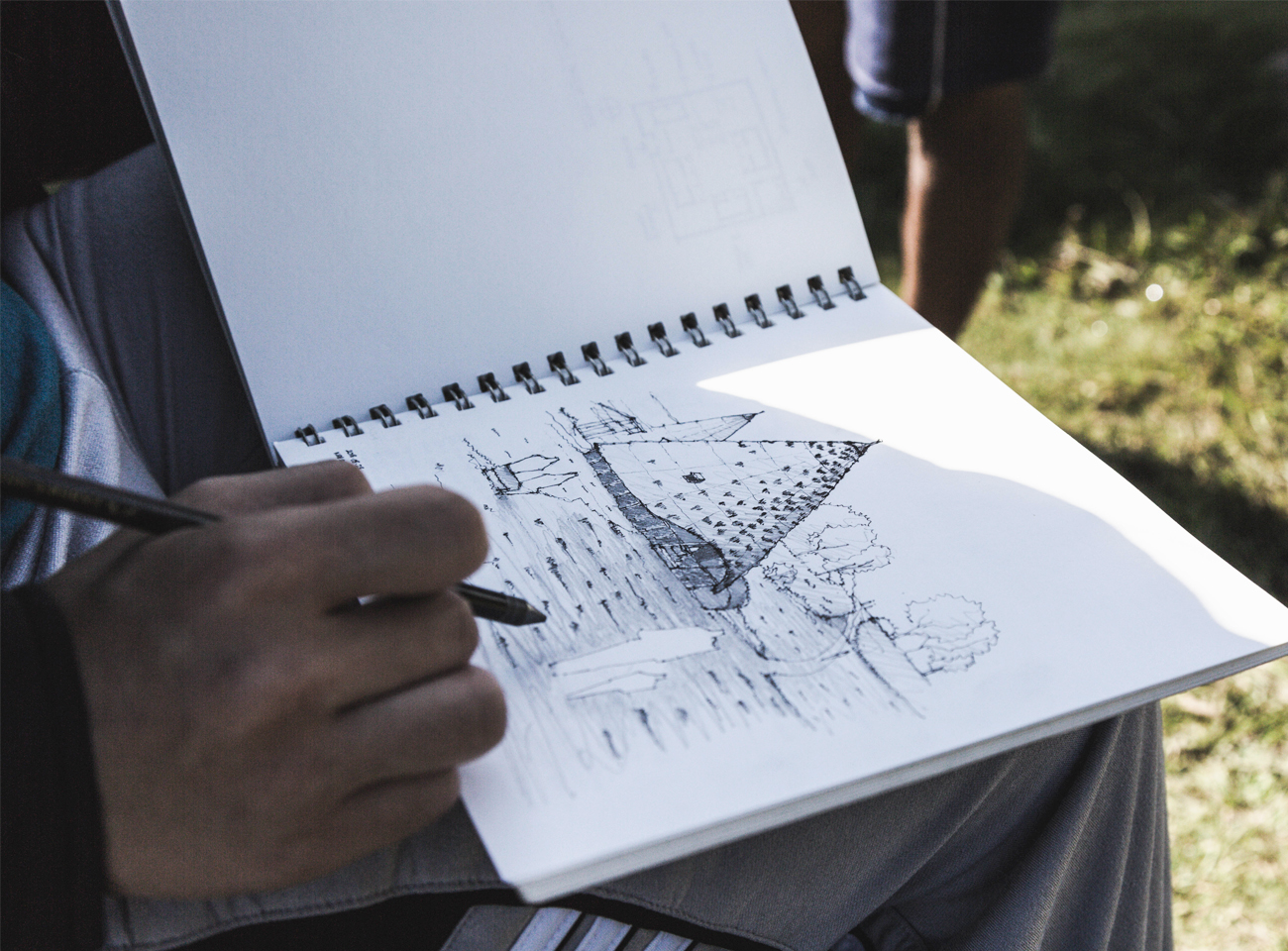

GM: It is surprising to me that Bob, apparently even as a student, did not draw much given that he is an extremely careful observer. But he has little patience and is always on the move, so the camera works best for him. The advantage of sketching over photography is that you are forced to analyze the architecture. The exercise required to produce a drawing necessitates a deeper understanding of a building and its components. You must carefully consider proportions, take measurements, and note sectional qualities of the space; these are all very important skills to develop as you learn about architecture. The advantage of using a camera is that you can easily create a record of a building and assemble your own photographic library over time. When you have a bad memory, like I do, it’s a great reference tool, and it rekindles your memory of the place. I enjoy focusing on details or elements that I may not be able to find in someone else’s photographs.

DL: You can examine photographs in retrospect, but you can’t move in the round as you can with a real building. Sketching forces you to observe things much more carefully while documenting the plan and/or section issues. The reality is that it’s hard enough to find time to draw when you’re traveling, especially when you’re on a short business trip with a tight schedule. The grand tours of the old days took six to eight months. Sometimes with the amount of time at hand available today, you end up having to do a combination of photography and drawing.

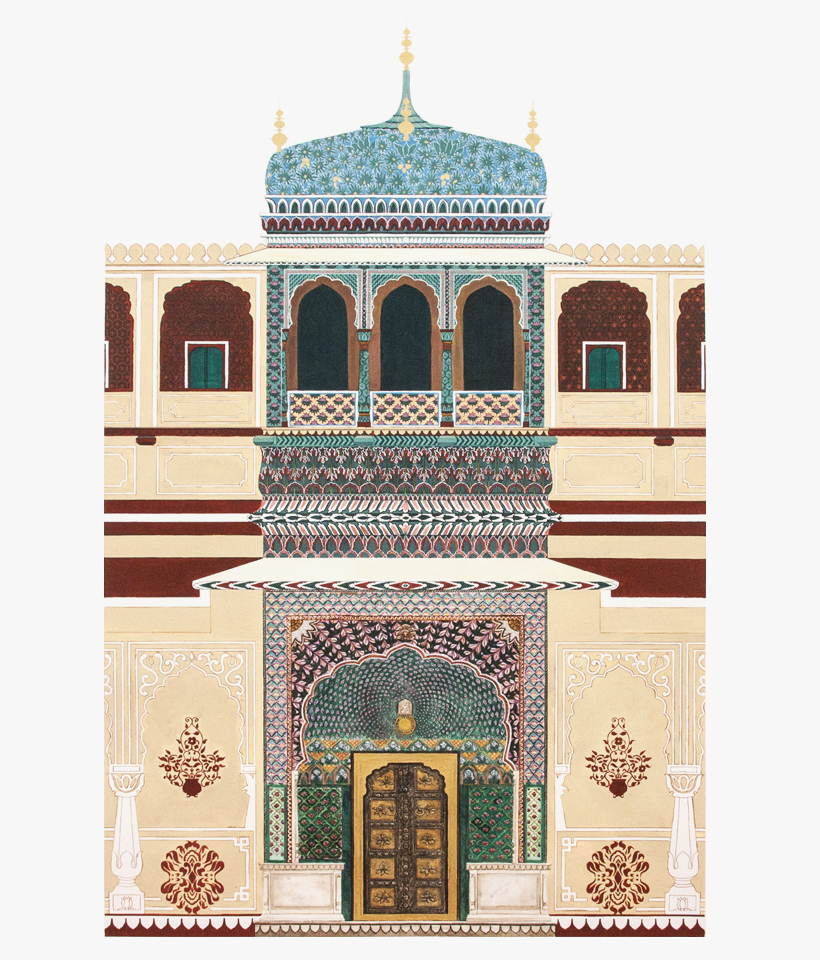

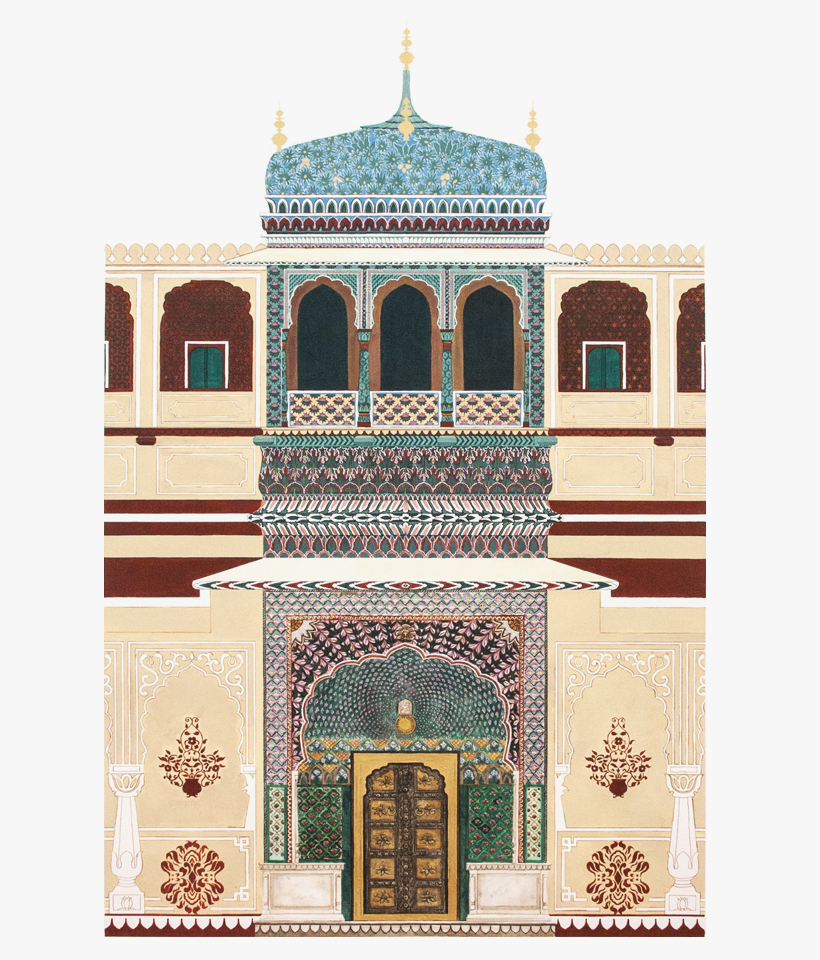

Rose Gate, City Palace of Jaipur, Rajasthan (Vidyadhar Bhattacharya and Sir Samuel Swinton Jacobs, 1729–32). Gouache over digital linework. Drawing Michelle Chen, 2015.

- Wae Rebo Village, Island of Flores, East Nusatenggara, Indonesia. Photograph Wilson Harkhono, 2018.

- Wilson Harkhono sketches in Wae Rebo Village, Island of Flores, East Nusatenggara, Indonesia. Photograph 2018.

- Church of St. Michael, Črna Vas, Ljubljana, Slovenia (Jože Plečnik, 1937−39). Photograph Kyle Schumann, 2017.

- Gadsisar Lake with small temples and shrines of Amar Sagar, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, India (c. 1400). Photograph Michelle Chen, 2015.

- An apprentice working at the Fujisato Woodshop, Fujisato, Akita, Japan. Photograph Anna Antropova, 2014.

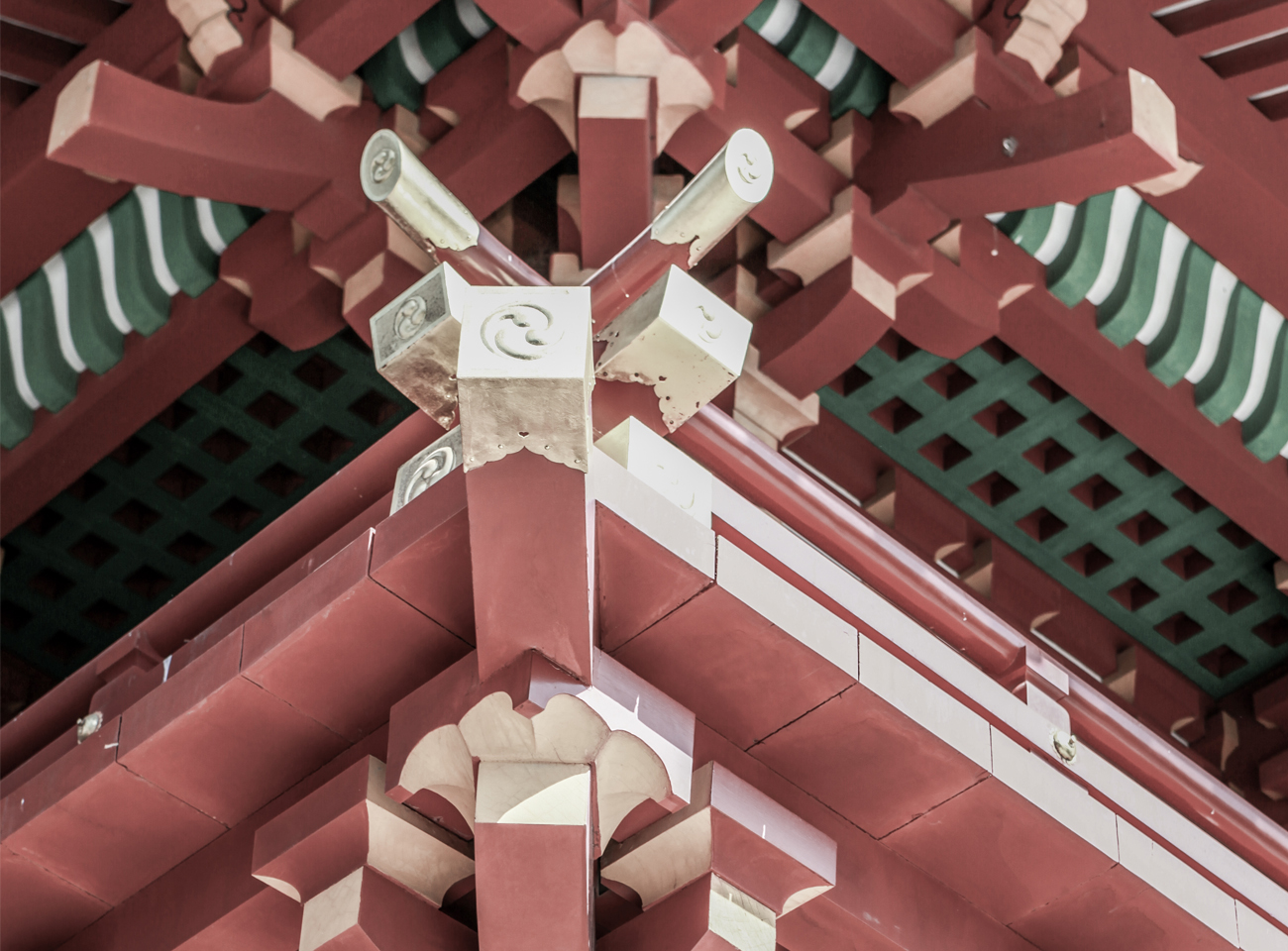

- Detail of a pagoda at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū, Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan. Photograph Anna Antropova, 2014.

- Detail of Caledonia Road Church, Glasgow, Scotland (Alexander Thomson, 1856–57). Photograph Gerald Bauer, 2016.

George de Brigard: I’m reminded of a selection of photographs that Bob took of Fraternity Row at Yale University right before we started to design Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin Colleges. They are pretty bad photographs! Bob is always joking that the weather is terrible when he travels, causing his photographs to be underexposed. But when you study the images as a series, in the order he took them, they tell you something that a single photograph cannot. There is a processional aspect to the sequence that is useful, as well as a value in studying them individually.

RR: The example of our work at Murray and Franklin Colleges is a good one. After all, research is a fundamental component of RAMSA’s design process and office culture. And travel is inherently also about precedent research—studying what has come before and how those buildings address site-specific issues. Can you talk about the ways in which the firm references and reinterprets precedents?

DL: At the start of any project we carefully research the appropriate conceptual underpinnings. We have our own travel experiences and personal archives to build from, and we use Bob’s library of travel slides as well. Over the years our office has amassed an incredible library—one of the most extensive private collections of architecture books anywhere and an unparalleled resource. We’ve moved offices a few times, and the space devoted to the library has expanded every time. Bob has certainly made a great effort to stay up to date on books and anything else that may help in terms of gathering information for our design efforts. We also established an in-office research department, acknowledging the importance of this kind of work, and it has contributed significantly to how we approach our design projects.

Radu-Remus Macovei presents his research to RAMSA staff. Photograph Peter Jakubowski, 2020.

Wilson Harkhono and Arianne Kouri prepare an exhibition of Harkhono’s fellowship research at RAMSA’s office in New York. Photograph Peter Jakubowski, 2019.

GM: The kind of research we do in the office is more scholarly than what is done by most other firms. It is quite remarkable how profoundly we research precedents to understand and develop the design facets of our projects.

MD: It’s also important to remember—and I think sometimes people outside this office don’t fully understand—that precedent research is about absorbing lessons from what has been done before and building upon them in our own work. We study both traditional and modern buildings, and curiously, traditional buildings are often very influential in our thinking about very modern-looking buildings, and vice versa. Often it’s a synthesis of both.

GB: Your comments circle back to the question of photography versus sketching and the difference between documenting and drawing in relation to precedent research. There is so much documentary evidence available with resources like Google—you can find a picture of almost anything. What’s missing, and what we must address as architects, is how that building can be analyzed and connected to other buildings or to a larger concept. This is what comes out in precedent research. The theme of the fellowship—tradition and invention—isn’t about bringing the totally obscure to light but rather it is about trying to generate connections. This is the rich activity that is offered by the fellowship.

Cover of Tradition and Invention: RAMSA Travel Fellowship 2013–17 (New York: RAMSA, 2018). Photograph Peter Jakubowski, 2019.

An earlier version of this text was first published in Tradition and Invention: RAMSA Travel Fellowship 2013–17 (New York: RAMSA, 2018), which documents the research of the first five fellows. To learn more about the RAMSA Fellowship, visit www.ramsa.com/fellowship.

RAMSA Partners Melissa DelVecchio, Daniel Lobitz, and Grant F. Marani served as jurors for the first ten years of the award. The current jurors are RAMSA Partners Bina Bhattacharyya, Johnny Cruz, and Preston Gumberich. The fellowship is administered by RAMSA Research: Director Arianne Kouri and Research Specialists Spenser A. Krut and Cole Wagner. Email fellowship@ramsa.com with any questions.

RAMSA Fellows: Jonathan Dessi-Olive, 2013; Anna Antropova, 2014; Michelle Chen, 2015; Gerald Bauer, 2016; Kyle Schumann, 2017; Wilson Harkhono, 2018; Radu-Remus Macovei, 2019; Yaxuan Liu, 2020; Daniel Hall, 2021; Giuliana Vaccarino Gearty, 2022; Neha Garg, 2023; Nga Ting (Joanna) Cheung, 2024; Zamen Lin, 2025.